Regionalism in Contemporary Czech Architecture

For good architects creating after the communist takeover in 1948, the goal was more about expressing belonging to the West than local identity. Architects who pursue architecture with a regionalist touch place greater emphasis on the "universal" dimension of their work. The problem also lies in the fact that in the older traditions of Czech architecture, it is difficult to distinguish a distinct vernacular.

Introduction

On February 21, 2006, I gave a lecture at the Museum of Applied Arts in Brno about architectural regionalism, emphasizing its manifestations in contemporary Czech architecture. Osamu Okamura, the editor-in-chief of Era 21, recorded the lecture and asked me to edit and shorten the written transcript. I decided to reduce the first part, which focused on various forms of 20th-century regionalism in the West. In the second part dedicated to the Czech scene, I will attempt to maintain the character of an extemporaneous speech and keep it approximately the same length.

The essence of architectural regionalism was captured by the main theorist of this trend, Kenneth Frampton, during lectures in Brno and Prague in 1995: "I travel across all continents, covering hundreds and thousands of kilometers, and yet I feel like I am still in the same place. This is because the same globalized architecture is being born everywhere today. And yet you should be able to tell from the architecture in which country and in which region you have found yourself." Frampton cites the work of Luís Barragán, Carlo Scarpa, Alvaro Siza, Sverre Fehn, Tadao Ando, Luigi Snozzi, or Rafael Moneo as good examples of locally specific architecture that expresses the identity of a particular region. All of these architects use the means of modern architecture but adapt them to local traditions. They are interested in how buildings in a given place have historically faced the climate, how they react to sunlight, how they settle in the landscape, and how this landscape has been shaped by human hands over centuries. They concentrate more on the environment of individual buildings rather than on the buildings themselves, which brings their work to the brink of architectural landscaping.

However, architectural regionalism has older roots, which Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre enlighteningly described in an article that Czech readers can find in the collection "Regionalism and Internationalism in Contemporary Architecture." If we overlook the earliest glimmers of interest in expressing national identity through architectural style, associated, for example, with the poet J. W. Goethe and his celebration of Gothic architecture as an expression of the German spirit, regionalism distinctly emerged on the scene in the second half of the 19th century, during the formation of modern European nations and the birth of modern nationalism. The "Czech" Neo-Renaissance of Antonín Wiehl sought to differentiate itself from the "universal," nationally undifferentiated Neo-Renaissance of Semper or Hansen. The organicism of Hungarian architect Ödön Lechner, the author of the Blue Church in Bratislava from 1907, stood in opposition to Otto Wagner's "universal" or imperial modernity. Political or nationalist undertones undoubtedly also characterized various "national styles" of the 1920s and 1930s, such as Janák's and Gočár's rondo-cubism or the German Heimatstil, whose "Old German" variant was showcased by architect F. G. Winter in the Hitlerjugendhaus building in Jihlava from 1940-1941. Nor did the variant of Soviet-oriented socialist realism, which bet on studying "progressive" national traditions, differ from them.

The types of architectural regionalism whose creators aimed to express the national soul or national sense of form through architectural style generally compromised themselves by their association with totalitarian political regimes. The democratic West has preferred modern architecture since the 1940s. Even after that, serious attempts at regionalist expression in Western countries often sought to adapt modern morphology to specific local conditions—in Brazil, Japan, Scandinavia, and the Mediterranean. The first attempts to synthesize modernist language with local dialects or vernaculars, associated with the work of Oscar Niemeyer, Kenzo Tange, Alvar Aalto, Jørn Utzon, or Ernesto Nathan Rogers and the BBPR group, were encapsulated under the term "modern regionalism" by Sigfried Giedion in later editions of the famous book Space, Time and Architecture. If we delve into the texts of these architects, we may find that their regard for the national soul has been replaced by an interest in the dialogue of building with climate, landscape, place, and context. They all know much about local architectural traditions and traditional technologies and materials, yet they avoid traditionalist stylistic expression. A member of the next generation of regionalists, who seeks to position themselves against both the nationalist variants of regionalism and the globalized architecture—hence Frampton refers to this generation as "critical"—Alvaro Siza described the relationship of modern regionalists to tradition with the often-cited phrase: "Tradition is a challenge to innovation."

The Beginnings of Modern Regionalism in Our Country

We have already touched on the Czech scene in the discussion of rondo-cubism or "national style" as an exemplary showcase of the nationalist variant of regionalism. The crematorium in Pardubice designed by Pavel Janák from 1923 aimed to express the idea of an Old Slavic sanctuary with its form, and the architect adorned it with decoration derived from folk ornamentation. At the same time, architect Bohuslav Fuchs, active from 1923 in Brno, built the Klostermann's lodge in Šumava. Fuchs also had nationalist tendencies at that time. He belonged to the Koliba association, which aimed to revive the Great Moravian Principality. However, at Klostermann's lodge, the architect realized that he was designing it for Šumava, and he built it in the spirit of how buildings had historically been constructed in those mountains—of wood and stone, featuring the typical stepped form of a roof. I consider it important that in this way, buildings in Šumava were not only erected by Czechs but predominantly by Germans, so there is nothing nationalist about Fuchs's Šumava vernacular—he was much more concerned with the specific place.

During the 1920s, Fuchs's stylistic expression changed, evolving towards functionalism, as demonstrated by his gymnasium in Jihlava from around 1930. Functionalism can be considered a pure international style. National or regional shades manifest only slightly in it. However, we should consider that at that time, Jihlava was more German than Czech, and Czech Germans were not inclined towards functionalism. When Fuchs used this style in this national context, functionalism might also resonate as a manifestation of Czech identity.

Shortly after the Jihlava gymnasium, Fuchs built his own cabin near Dolní Loučky. It resembles functionalism translated into wood. I do not know whether the architect considered wooden cabins to be something specifically Czech, but we already know that it truly was a kind of national pastime that had not taken hold to such an extent elsewhere in Europe. We might even speak of a cabin vernacular in our country, especially since the cabins resemble popularized functionalism. And some contemporary Czech architects have drawn lessons from it.

Just before World War II, Fuchs developed a colony of workers' houses for a textile factory, again near Dolní Loučky. Here, the architect draws evidently from the typical features of rural architecture on the southeastern edge of the Czech-Moravian Highlands, thus manifesting himself as a deliberate regionalist. Many village buildings in the surrounding area have a construction of stone posts or cross walls, onto which a wooden wall is hung, and Fuchs did the same.

After World War II, a debate about regionalism developed in our country that responded to trends in the world. At that time, Oscar Niemeyer emerged in Brazil, Aalto became famous, and the Japanese scene began to awaken with Kenzo Tange at the forefront. Architect Emanuel Hruška published a book titled Urbanistická forma (Urban Form) in 1947. He questioned whether regionalism had a right to exist in our country but arrived at skeptical conclusions. He stated that such a direction could only arise if there was a strong distinguishable construction tradition, and he said that no such tradition exists here, that all domestic traditions were too weak to provide a regionalist foundation for contemporary architecture. And, indeed, when we ask ourselves what architectural traits are specific to our territory, we find it difficult to arrive at clear conclusions. Let us not think of folk, folkloric architecture, from which Kotěra or Jurkovič drew. While we can easily distinguish them by regions, a modern architect, even a regionalist, could hardly use their features. Modern regionalists are more interested in simple architecture of small towns rather than pure folklore. And it is precisely this small-town vernacular that is difficult to identify in our country compared to other European countries; we have nothing to grasp.

Somewhat less skeptically, the possibilities of modern Czech regionalism were viewed by Karel Honzík in the essay "Reflection on the Expression of Czech Construction," published in 1948 in Architektura ČSR. For the Thonet company, Honzík incidentally built a significantly regionalist residential house in Bystřice pod Hostýnem. According to this creator, there are indeed distinguishable features in the older traditions of Czech architecture. What characterizes Czech architecture of the 19th century, but also Czech functionalism? For example, clumsiness, Honzík claims, when comparing Czech buildings with French ones. Furthermore, Czech architecture supposedly lacks a strong tension between horizontals and verticals; it is deficient in artistry. As we see, Honzík can specify distinct traits of Czech architecture, but he is not very enthusiastic about them.

Bohuslav Fuchs entered the debate, who wrote an article on regionalism for the Brno magazine Blok around 1947, and he was again quite skeptical. Although he himself designed regionalist buildings, he stated here that regionalism has justification only where there are significant climatic differences compared to Europe. Brazilian regionalism thus seems legitimate to Fuchs, while Czech regionalism does not.

Anti-regionalist Sentiments of the Socialist Period

In the era of socialist realism after 1948, Czech architects had to cultivate regionalism by obligation, in the spirit of Stalin's definition of socialist realism as art that is socialist in content and national in form. They pondered what "progressive" domestic traditions they could use for this national form. Sometimes they turned to Renaissance and Neo-Renaissance, at other times to folk architecture, as evidenced by the socialist village Zvírotice at the Slapská dam by Hana Stašková and Jaroslav Kándl.

The traumatic experience with this kind of politically dictated regionalism is probably one of the main reasons why modern regionalism did not take root in our country. The Kralice Bible Museum in Kralice, surprisingly, is one of the rare exceptions, also Fuchs's work from 1968, but we would find very few other examples like it.

I consider the second important reason for the indifference towards regionalism to be the fact that truly good Czech architects of the socialist period always tried more to express our belonging to the West through their buildings than any local identity. Therefore, they were not afraid to directly quote famous Western buildings, as the Šrámek brothers did in Prague at Můstek when they blatantly drew inspiration for the ČKD building from a well-known American work by César Pelli in 1976.

The 1990s - The Phenomenon of the "Second City"

After the Velvet Revolution, the starting conditions for cultivating domestic regionalist architecture did not seem very good. And there are not particularly numerous efforts towards it either. Nevertheless, I will try to point out some of them.

I must say in advance that I consider Brno to be the most promising breeding ground for contemporary regionalism in our country, that is, a relatively large city. However, it has always been the case in the world that the countryside itself could not become a productive source of regionalist architecture. Such architecture is rather born in cities, but not in the main, central ones. Take Alvaro Siza in Portugal. He does not have an office in the center, in Lisbon, but in a smaller Portuguese city, Porto. The Japanese Tadao Ando does not reside in Tokyo, but creates in Kyoto and Osaka. The Mexican Luís Barragán did not start in Mexico City, but in Guadalajara, a large though not central Mexican city. Luigi Snozzi does not reside in Bern or Basel, but in Ticino, on the edge of Switzerland.

Brno occupies a similar position as a second city in this regard. It has always sought to define itself against the center, Prague, and we all know that "Praguers" are not very fond of "Brňáci." This need not lead only to unproductive grumpiness but also to positive cultural actions. However, demarcation against the center is not enough. Regionalism must find deeper reasons, deeper legitimacy for itself. This is why I am interested in the opinions of leading Brno architects Petr Hrůša and Petr Pelčák, and the reason why, although they practice regionalism, they reject it in theory.

For Hrůša, Pelčák, and the broader generational group of members of the Brno association Obecní dům, it seems typical that they systematically explore newer traditions of Brno architecture, what happened in Brno in the first half of the 20th century. This has already resulted in many remarkable exhibitions and exhibition catalogs. When you further read the writings of Petr Pelčák, you will find that he seeks to define the broader cultural circle to which Brno belongs, and concludes that at least in the first half of the 20th century, there was something like a cultural triangle between Vienna, Brno, and Bratislava. This region was characterized by a peculiar purist creation, a kind of purist neoclassicism that is not yet functionalist. In Vienna, figures like Josef Frank or Oskar Strnad manifested it, in Bratislava Fridrich Weinwurm, and in Brno Ernst Wiesner, Hrůša's and Pelčák's idol. Pelčák's fondness for Wiesner's work is counterbalanced by the criticism of another great Brno architect, the often-cited Bohuslav Fuchs. When the centenary of Fuchs's birth took place in 1995, Pelčák presented a paper contrasting Wiesner's and Fuchs's architecture at a conference. Wiesner's buildings are supposedly tailored to the human scale, use traditional materials, are robust and solid, and withstand time better than Fuchs's overly experimental functionalism. Thus, Wiesner got a chance to become a source of inspiration for today's Brno regionalism, and if you look at Burian and Křivinka's Geodis in Židenice or some of Hrůša's and Pelčák's projects, Wiesner's background is clearly noticeable in them.

However, programmatic regionalism, even Wiesner's, is explicitly rejected by Hrůša and, especially, Pelčák. This rejection of regionalism has a deeper reason in their thinking. Pelčák states that good architecture must be well constructed, not assembled, and that it must have a universal, even metaphysical dimension. Regionalism binds you too closely to context, to place, but you must balance this bond with a universal dimension that should be the same everywhere. Good architecture should relate to God everywhere in the world, says Pelčák, as if he has just finished reading the writings of English romantics Pugin or Ruskin, while its relationship to the place and region appears to them as secondary. This metaphysical dimension surely also concerned another Brno architect from the Obecní dům circle, Ladislav Kuba, when he designed the undoubtedly regionalist building of the Chapel of the Virgin Mary in Jestřebí.

When I still say that some of Pelčák's and Hrůša's buildings resonate regionally, this certainly applies to the building of Povodí Moravy in Olomouc. The building sensitively responds to its place, to the bend of the Morava River beyond Olomouc, is solidly constructed from traditional materials, and firmly stands on the ground. With its brick walls and stone base, it recalls old industrial buildings that were built during the Austro-Hungarian Empire and directly in the Olomouc region. The highly projecting cornice, along with windows embedded in the face, also resembles the works from Otto Wagner's school, as Pavel Zatloukal has noted. However, it also carries something from Ernst Wiesner, particularly in how it quotes the neighboring Wiesner building from the 1920s.

Is There a Central European Architecture?

In 1998, a conference on contemporary Central European architecture took place in Zlín, the conclusions of which can be found in a collection published by the local regional gallery. Participants examined whether regionalist tendencies are manifesting in the architecture of Central European states and whether a tendency to express Central European identity is evident in this region. However, the results were skeptical, perhaps with the exception of Hungary and its Makovecz school. And not only that. The attempt at a debate ended with the entry of Austrian historian of modern architecture Jan Tabor, who declared, and Petr Pelčák immediately joined him, that Central Europe does not exist at all. According to Tabor, Central Europe is merely a conceptual construct, a figment of the author of the book Dunaj, Claudio Magris, and American university intellectuals. The audience was taken aback by this statement, and no debate developed around it.

However, traces of the debate on whether the Central European region exists and whether it is characterized by a specific architecture could still be found in Czech architectural magazines. With a positive answer to these questions, for example, Ladislav Lábus spoke. According to him, distinguishable characteristics of Central European architectural tradition lie in a special gradation of architectural volumes, their specific squeezing and piling, and in a peculiar layering of styles and various architectural languages. When we look at Lábus's completion of the Langhans Palace in Prague in Vodičkova Street, the small house near the Franciscan Garden resonates neo-functionalistically, while an almost Wiesner-like house with windows rises above it, but it is topped by a translucent upper structure in a minimalist style. In one architectural work, three architectural languages thus overlap.

Recently, Alexandr Skalický entered the debate with an interesting contribution. In the book Megastore, you will find his opinion that contemporary regionalism makes sense, but only when the relevant region can be creative. When the local culture only accepts stimuli from the center, such regionalism leads only to parochialism, and that is not worth cultivating.

Techniques of Czech Regionalist Architecture

The small house by Skalický and Archteam from Náchod in the village of Mořina near Karlštejn is probably not an entirely regionalist building. The authors aimed more for archetypality, for the simplest house with a roof and windows. However, if you walk around Mořina, you will see several very similar old barns. And this likely represents one way architects define local vernacular in our country. They seek what is typical in rural or village architecture.

The typical image of village architecture surely also informs Kuba's chapel in Jestřebí, or, for example, the family house in Dobřejovice near Prague by architects Poláček and Škarda, whose sloping roof recalls the lean-tos around the yards of village homes. The house by Markéta Cajthamlová in Počernice near Prague is based on the foundations of a vanished farm, replicating its proportions and layout, yet its style is more influenced by the traditions of modern European regionalism than by Czech village vernacular.

A special attempt at rural architecture is the family house in Hodonín by Zdeněk Fránek. The author here aimed not so much at evoking village buildings but rather at typical objects of village life. To some, the house may recall a jug; Fránek himself speaks directly of a bag.

But why should we only be inspired by old village buildings when searching for vernacular? The typical image of the Czech countryside also comprises much younger structures. I mean the so-called steel barns that have spread across the rural landscape in the last thirty years almost to the same extent as panel houses in cities. I would not be far off in saying that the model for Hrůša's and Pelčák's tennis club on the outskirts of Litomyšl was such a steel barn.

The second path to achieving a regional Czech vernacular involves imitating cabins and summer houses. I repeat, you will not find as many wooden cottages anywhere else in Europe as here. When Svatopluk Sládeček and Luděk del Maschio designed the municipal office in the village of Šarovy near Zlín, they evidently followed the language of cabins. Something similar applies to Sládeček's family house in Rajhrad near Brno or the wooden buildings of Kopřivnice architect Kamil Mrva.

Figures and Barbarians

At Sládeček, I must digress. I find it important that some of his houses are labeled as figurative. American postmodernists, such as Michael Graves, wrote about figurative architecture, suggesting that a building benefits from reminding us of some animal or object. The small house in Rajhrad is referred to by Sládeček as "television" or "screen," and soon we will see "a gopher" from him. But I am interested in the ironic diminutive—"figurkativity" instead of "figurativity." I believe that Sváťa touches on something deeply Czech here, something that transcends the realm of architecture: typically Czech human types, typically non-heroic, non-gallant, as depicted in the prose of Neruda, Hašek, or Hrabal. Perhaps it is from here, from "Tales from the Lesser Town" or from Švejk, that the path to Czech regionalism can lead.

The question of something typically Czech was also posed by David Kraus, the author of the wooden family house in Říčany near Prague. He pondered how Czech culture differs from Western culture and concluded that it lies in the degree of cultivation. We Czechs, nor Czech architects, will never reach Western cultivation. Therefore, we have no choice but to cultivate our Czech barbarism and turn it into a positive.

Czech Sun

If we want to know what is specific to Czech or Central European architectural tradition, it pays to ask foreigners, foreign architects, and architecture historians about it. We ourselves are too embedded in our environment and do not have sufficient distance from it. I once read an interview with Norwegian architecture historian Christian Norberg-Schulz, the author of the book Genius loci, and I also heard what Frank Gehry says about Central European or directly Prague architecture. They both agreed that Czech or Central European architecture has almost always been characterized by being plastered and that its creators could play gently with light and shadows on plastered facades.

I believe that Josef Pleskot utilized the same insight during the renovation of the town hall in Benešov. At the back wing, he played with the varying depths of the façade openings, dark at the arcade and lighter in the upper floors. The top floor of the town hall facing the square then curves back to create a gentle arc in the shadow.

Back to Techniques: Walls, Paving

Pleskot, like Lábus or Jan Línek, readily admits that part of his work has a regionalist character. In Línek's case, we could even trace the inspiration of rural architecture, which I have already mentioned. The irregular layout of the residential farm in Kostelec nad Černými lesy was traced by Línek from one farm in Strakonice, whose images he found in Václav Mencl's book Czech Folk Architecture. But now I will be interested in the carefully arranged stone walls that Línek encircled the garden of the Kostelec farm with.

I said that famous Western regionalists are half architects and half landscapists, and they are interested in the ways people have transformed the landscape over the centuries. Snozzi incorporates ancient terraces at the foothills of the Swiss Alps into his buildings; the Venetian Scarpa liked to use water channels and ditches.

One such ancient way of transforming the landscape can also be found in our country. If you look at old maps of Czech towns and villages, you will find that thin, long plots or gardens extend from every house. Such plots have historically been separated from each other by stone walls.

A remnant of such a wall also stood behind the residential farm in Kostelec nad Černými lesy. Línek had it carefully restored because he considered it important for his concept. There is nothing regionalist about the houses with starter apartments in Horažďovice designed by Josef Pleskot—except for the careful reconstruction of the stone wall that delineates its plot. Pleskot also equipped a villa in Lipence near Zbraslav with a wall, with an upper structure in the spirit of cabin vernacular on a vast flat roof.

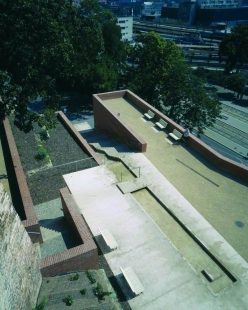

Sometimes an architect's intervention may be limited to the wall itself, bypassing the roof. For such a landscape treatment rather than purely architectural improvement, Zdenka Vydrová is indebted for the sub-mansion in Litomyšl, a connecting path between the parking lot and the castle, which the architect surrounded with walls and carefully paved. I generally believe that very typical regionalist tasks include the improvement of public spaces, such as the one demonstrated by Petr Hrůša and Petr Pelčák in the park under the Petrov hill in Brno. Finally, paving can also be considered a product of regionalism, especially when it seeks to achieve a traditional and time-non-specific appearance. In Hana Zachová's pavements in Český Krumlov, we cannot be sure when they were actually created, and thus they resonate regionally, while the paving in the courtyard of the Archdiocesan Museum in Olomouc by the team of Hájek-Hradečný-Šépka does not disguise its authors’ fondness for modern abstract art and does not belong within the framework of regionalism.

Citing Regionalism from Abroad

The techniques of Czech regionalism are not sufficiently developed yet. Even those architects who are not afraid of identifying with this trend often do not know how to express their regionalist ambition well. It is not surprising, therefore, that some of them openly cite the works of famous regionalist architects from the West. The family house in Míkovice near Uherské Hradiště is called "gopher" by Svatopluk Sládeček. However, I call it "Alvaro Siza" because it looks like a simplified version of one of the towers in the complex of Siza's Faculty of Architecture in Porto. The details of an excellent regionalist house in Prague-Hlubočepy by Barbora Rossi and Jan Mrázek remind us of the works of Italian representatives of this trend, such as Scarpa's adaptation of the Tolentini Monastery in Venice or the house of Gino Zucchi on the Venetian island of Giudecca.

Conclusion

I do not believe that regionalism should be the only path of contemporary architecture. It can comfortably remain on the periphery. However, there are reasons that justify its survival, and thus regionalist creation will not disappear from the scene in our country either. Primarily, I mean the resistance to globalized architecture.

Looking at the Hlubočepy house by the Rossi-Mrázek team, another undeniable quality of regionalist architecture comes to mind, especially important for Czech lands with such a high number of preserved historical settlements. Regionalist buildings simply fit well into historical contexts. Although this trend does not offer a single correct method for how contemporary architecture should enter a historic city, it provides a guarantee that you will not make a major mistake in the process.

ERA 21 - Low-Budget Architecture and the Identity of Place

a professional architectural bimonthly

Era 21 has earned a reputation as a quality professional magazine during its five-year existence, with each issue thematically elaborated. The careful selection of profile topics that also open discussions on issues that have previously remained in "professional ignorance" has contributed to the very positive reader response.

> table of contents of issue 3/2006

> subscription order

Introduction

On February 21, 2006, I gave a lecture at the Museum of Applied Arts in Brno about architectural regionalism, emphasizing its manifestations in contemporary Czech architecture. Osamu Okamura, the editor-in-chief of Era 21, recorded the lecture and asked me to edit and shorten the written transcript. I decided to reduce the first part, which focused on various forms of 20th-century regionalism in the West. In the second part dedicated to the Czech scene, I will attempt to maintain the character of an extemporaneous speech and keep it approximately the same length.

The essence of architectural regionalism was captured by the main theorist of this trend, Kenneth Frampton, during lectures in Brno and Prague in 1995: "I travel across all continents, covering hundreds and thousands of kilometers, and yet I feel like I am still in the same place. This is because the same globalized architecture is being born everywhere today. And yet you should be able to tell from the architecture in which country and in which region you have found yourself." Frampton cites the work of Luís Barragán, Carlo Scarpa, Alvaro Siza, Sverre Fehn, Tadao Ando, Luigi Snozzi, or Rafael Moneo as good examples of locally specific architecture that expresses the identity of a particular region. All of these architects use the means of modern architecture but adapt them to local traditions. They are interested in how buildings in a given place have historically faced the climate, how they react to sunlight, how they settle in the landscape, and how this landscape has been shaped by human hands over centuries. They concentrate more on the environment of individual buildings rather than on the buildings themselves, which brings their work to the brink of architectural landscaping.

However, architectural regionalism has older roots, which Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre enlighteningly described in an article that Czech readers can find in the collection "Regionalism and Internationalism in Contemporary Architecture." If we overlook the earliest glimmers of interest in expressing national identity through architectural style, associated, for example, with the poet J. W. Goethe and his celebration of Gothic architecture as an expression of the German spirit, regionalism distinctly emerged on the scene in the second half of the 19th century, during the formation of modern European nations and the birth of modern nationalism. The "Czech" Neo-Renaissance of Antonín Wiehl sought to differentiate itself from the "universal," nationally undifferentiated Neo-Renaissance of Semper or Hansen. The organicism of Hungarian architect Ödön Lechner, the author of the Blue Church in Bratislava from 1907, stood in opposition to Otto Wagner's "universal" or imperial modernity. Political or nationalist undertones undoubtedly also characterized various "national styles" of the 1920s and 1930s, such as Janák's and Gočár's rondo-cubism or the German Heimatstil, whose "Old German" variant was showcased by architect F. G. Winter in the Hitlerjugendhaus building in Jihlava from 1940-1941. Nor did the variant of Soviet-oriented socialist realism, which bet on studying "progressive" national traditions, differ from them.

The types of architectural regionalism whose creators aimed to express the national soul or national sense of form through architectural style generally compromised themselves by their association with totalitarian political regimes. The democratic West has preferred modern architecture since the 1940s. Even after that, serious attempts at regionalist expression in Western countries often sought to adapt modern morphology to specific local conditions—in Brazil, Japan, Scandinavia, and the Mediterranean. The first attempts to synthesize modernist language with local dialects or vernaculars, associated with the work of Oscar Niemeyer, Kenzo Tange, Alvar Aalto, Jørn Utzon, or Ernesto Nathan Rogers and the BBPR group, were encapsulated under the term "modern regionalism" by Sigfried Giedion in later editions of the famous book Space, Time and Architecture. If we delve into the texts of these architects, we may find that their regard for the national soul has been replaced by an interest in the dialogue of building with climate, landscape, place, and context. They all know much about local architectural traditions and traditional technologies and materials, yet they avoid traditionalist stylistic expression. A member of the next generation of regionalists, who seeks to position themselves against both the nationalist variants of regionalism and the globalized architecture—hence Frampton refers to this generation as "critical"—Alvaro Siza described the relationship of modern regionalists to tradition with the often-cited phrase: "Tradition is a challenge to innovation."

The Beginnings of Modern Regionalism in Our Country

We have already touched on the Czech scene in the discussion of rondo-cubism or "national style" as an exemplary showcase of the nationalist variant of regionalism. The crematorium in Pardubice designed by Pavel Janák from 1923 aimed to express the idea of an Old Slavic sanctuary with its form, and the architect adorned it with decoration derived from folk ornamentation. At the same time, architect Bohuslav Fuchs, active from 1923 in Brno, built the Klostermann's lodge in Šumava. Fuchs also had nationalist tendencies at that time. He belonged to the Koliba association, which aimed to revive the Great Moravian Principality. However, at Klostermann's lodge, the architect realized that he was designing it for Šumava, and he built it in the spirit of how buildings had historically been constructed in those mountains—of wood and stone, featuring the typical stepped form of a roof. I consider it important that in this way, buildings in Šumava were not only erected by Czechs but predominantly by Germans, so there is nothing nationalist about Fuchs's Šumava vernacular—he was much more concerned with the specific place.

During the 1920s, Fuchs's stylistic expression changed, evolving towards functionalism, as demonstrated by his gymnasium in Jihlava from around 1930. Functionalism can be considered a pure international style. National or regional shades manifest only slightly in it. However, we should consider that at that time, Jihlava was more German than Czech, and Czech Germans were not inclined towards functionalism. When Fuchs used this style in this national context, functionalism might also resonate as a manifestation of Czech identity.

Shortly after the Jihlava gymnasium, Fuchs built his own cabin near Dolní Loučky. It resembles functionalism translated into wood. I do not know whether the architect considered wooden cabins to be something specifically Czech, but we already know that it truly was a kind of national pastime that had not taken hold to such an extent elsewhere in Europe. We might even speak of a cabin vernacular in our country, especially since the cabins resemble popularized functionalism. And some contemporary Czech architects have drawn lessons from it.

Just before World War II, Fuchs developed a colony of workers' houses for a textile factory, again near Dolní Loučky. Here, the architect draws evidently from the typical features of rural architecture on the southeastern edge of the Czech-Moravian Highlands, thus manifesting himself as a deliberate regionalist. Many village buildings in the surrounding area have a construction of stone posts or cross walls, onto which a wooden wall is hung, and Fuchs did the same.

After World War II, a debate about regionalism developed in our country that responded to trends in the world. At that time, Oscar Niemeyer emerged in Brazil, Aalto became famous, and the Japanese scene began to awaken with Kenzo Tange at the forefront. Architect Emanuel Hruška published a book titled Urbanistická forma (Urban Form) in 1947. He questioned whether regionalism had a right to exist in our country but arrived at skeptical conclusions. He stated that such a direction could only arise if there was a strong distinguishable construction tradition, and he said that no such tradition exists here, that all domestic traditions were too weak to provide a regionalist foundation for contemporary architecture. And, indeed, when we ask ourselves what architectural traits are specific to our territory, we find it difficult to arrive at clear conclusions. Let us not think of folk, folkloric architecture, from which Kotěra or Jurkovič drew. While we can easily distinguish them by regions, a modern architect, even a regionalist, could hardly use their features. Modern regionalists are more interested in simple architecture of small towns rather than pure folklore. And it is precisely this small-town vernacular that is difficult to identify in our country compared to other European countries; we have nothing to grasp.

Somewhat less skeptically, the possibilities of modern Czech regionalism were viewed by Karel Honzík in the essay "Reflection on the Expression of Czech Construction," published in 1948 in Architektura ČSR. For the Thonet company, Honzík incidentally built a significantly regionalist residential house in Bystřice pod Hostýnem. According to this creator, there are indeed distinguishable features in the older traditions of Czech architecture. What characterizes Czech architecture of the 19th century, but also Czech functionalism? For example, clumsiness, Honzík claims, when comparing Czech buildings with French ones. Furthermore, Czech architecture supposedly lacks a strong tension between horizontals and verticals; it is deficient in artistry. As we see, Honzík can specify distinct traits of Czech architecture, but he is not very enthusiastic about them.

Bohuslav Fuchs entered the debate, who wrote an article on regionalism for the Brno magazine Blok around 1947, and he was again quite skeptical. Although he himself designed regionalist buildings, he stated here that regionalism has justification only where there are significant climatic differences compared to Europe. Brazilian regionalism thus seems legitimate to Fuchs, while Czech regionalism does not.

Anti-regionalist Sentiments of the Socialist Period

In the era of socialist realism after 1948, Czech architects had to cultivate regionalism by obligation, in the spirit of Stalin's definition of socialist realism as art that is socialist in content and national in form. They pondered what "progressive" domestic traditions they could use for this national form. Sometimes they turned to Renaissance and Neo-Renaissance, at other times to folk architecture, as evidenced by the socialist village Zvírotice at the Slapská dam by Hana Stašková and Jaroslav Kándl.

The traumatic experience with this kind of politically dictated regionalism is probably one of the main reasons why modern regionalism did not take root in our country. The Kralice Bible Museum in Kralice, surprisingly, is one of the rare exceptions, also Fuchs's work from 1968, but we would find very few other examples like it.

I consider the second important reason for the indifference towards regionalism to be the fact that truly good Czech architects of the socialist period always tried more to express our belonging to the West through their buildings than any local identity. Therefore, they were not afraid to directly quote famous Western buildings, as the Šrámek brothers did in Prague at Můstek when they blatantly drew inspiration for the ČKD building from a well-known American work by César Pelli in 1976.

The 1990s - The Phenomenon of the "Second City"

After the Velvet Revolution, the starting conditions for cultivating domestic regionalist architecture did not seem very good. And there are not particularly numerous efforts towards it either. Nevertheless, I will try to point out some of them.

I must say in advance that I consider Brno to be the most promising breeding ground for contemporary regionalism in our country, that is, a relatively large city. However, it has always been the case in the world that the countryside itself could not become a productive source of regionalist architecture. Such architecture is rather born in cities, but not in the main, central ones. Take Alvaro Siza in Portugal. He does not have an office in the center, in Lisbon, but in a smaller Portuguese city, Porto. The Japanese Tadao Ando does not reside in Tokyo, but creates in Kyoto and Osaka. The Mexican Luís Barragán did not start in Mexico City, but in Guadalajara, a large though not central Mexican city. Luigi Snozzi does not reside in Bern or Basel, but in Ticino, on the edge of Switzerland.

Brno occupies a similar position as a second city in this regard. It has always sought to define itself against the center, Prague, and we all know that "Praguers" are not very fond of "Brňáci." This need not lead only to unproductive grumpiness but also to positive cultural actions. However, demarcation against the center is not enough. Regionalism must find deeper reasons, deeper legitimacy for itself. This is why I am interested in the opinions of leading Brno architects Petr Hrůša and Petr Pelčák, and the reason why, although they practice regionalism, they reject it in theory.

For Hrůša, Pelčák, and the broader generational group of members of the Brno association Obecní dům, it seems typical that they systematically explore newer traditions of Brno architecture, what happened in Brno in the first half of the 20th century. This has already resulted in many remarkable exhibitions and exhibition catalogs. When you further read the writings of Petr Pelčák, you will find that he seeks to define the broader cultural circle to which Brno belongs, and concludes that at least in the first half of the 20th century, there was something like a cultural triangle between Vienna, Brno, and Bratislava. This region was characterized by a peculiar purist creation, a kind of purist neoclassicism that is not yet functionalist. In Vienna, figures like Josef Frank or Oskar Strnad manifested it, in Bratislava Fridrich Weinwurm, and in Brno Ernst Wiesner, Hrůša's and Pelčák's idol. Pelčák's fondness for Wiesner's work is counterbalanced by the criticism of another great Brno architect, the often-cited Bohuslav Fuchs. When the centenary of Fuchs's birth took place in 1995, Pelčák presented a paper contrasting Wiesner's and Fuchs's architecture at a conference. Wiesner's buildings are supposedly tailored to the human scale, use traditional materials, are robust and solid, and withstand time better than Fuchs's overly experimental functionalism. Thus, Wiesner got a chance to become a source of inspiration for today's Brno regionalism, and if you look at Burian and Křivinka's Geodis in Židenice or some of Hrůša's and Pelčák's projects, Wiesner's background is clearly noticeable in them.

However, programmatic regionalism, even Wiesner's, is explicitly rejected by Hrůša and, especially, Pelčák. This rejection of regionalism has a deeper reason in their thinking. Pelčák states that good architecture must be well constructed, not assembled, and that it must have a universal, even metaphysical dimension. Regionalism binds you too closely to context, to place, but you must balance this bond with a universal dimension that should be the same everywhere. Good architecture should relate to God everywhere in the world, says Pelčák, as if he has just finished reading the writings of English romantics Pugin or Ruskin, while its relationship to the place and region appears to them as secondary. This metaphysical dimension surely also concerned another Brno architect from the Obecní dům circle, Ladislav Kuba, when he designed the undoubtedly regionalist building of the Chapel of the Virgin Mary in Jestřebí.

When I still say that some of Pelčák's and Hrůša's buildings resonate regionally, this certainly applies to the building of Povodí Moravy in Olomouc. The building sensitively responds to its place, to the bend of the Morava River beyond Olomouc, is solidly constructed from traditional materials, and firmly stands on the ground. With its brick walls and stone base, it recalls old industrial buildings that were built during the Austro-Hungarian Empire and directly in the Olomouc region. The highly projecting cornice, along with windows embedded in the face, also resembles the works from Otto Wagner's school, as Pavel Zatloukal has noted. However, it also carries something from Ernst Wiesner, particularly in how it quotes the neighboring Wiesner building from the 1920s.

Is There a Central European Architecture?

In 1998, a conference on contemporary Central European architecture took place in Zlín, the conclusions of which can be found in a collection published by the local regional gallery. Participants examined whether regionalist tendencies are manifesting in the architecture of Central European states and whether a tendency to express Central European identity is evident in this region. However, the results were skeptical, perhaps with the exception of Hungary and its Makovecz school. And not only that. The attempt at a debate ended with the entry of Austrian historian of modern architecture Jan Tabor, who declared, and Petr Pelčák immediately joined him, that Central Europe does not exist at all. According to Tabor, Central Europe is merely a conceptual construct, a figment of the author of the book Dunaj, Claudio Magris, and American university intellectuals. The audience was taken aback by this statement, and no debate developed around it.

However, traces of the debate on whether the Central European region exists and whether it is characterized by a specific architecture could still be found in Czech architectural magazines. With a positive answer to these questions, for example, Ladislav Lábus spoke. According to him, distinguishable characteristics of Central European architectural tradition lie in a special gradation of architectural volumes, their specific squeezing and piling, and in a peculiar layering of styles and various architectural languages. When we look at Lábus's completion of the Langhans Palace in Prague in Vodičkova Street, the small house near the Franciscan Garden resonates neo-functionalistically, while an almost Wiesner-like house with windows rises above it, but it is topped by a translucent upper structure in a minimalist style. In one architectural work, three architectural languages thus overlap.

Recently, Alexandr Skalický entered the debate with an interesting contribution. In the book Megastore, you will find his opinion that contemporary regionalism makes sense, but only when the relevant region can be creative. When the local culture only accepts stimuli from the center, such regionalism leads only to parochialism, and that is not worth cultivating.

Techniques of Czech Regionalist Architecture

The small house by Skalický and Archteam from Náchod in the village of Mořina near Karlštejn is probably not an entirely regionalist building. The authors aimed more for archetypality, for the simplest house with a roof and windows. However, if you walk around Mořina, you will see several very similar old barns. And this likely represents one way architects define local vernacular in our country. They seek what is typical in rural or village architecture.

The typical image of village architecture surely also informs Kuba's chapel in Jestřebí, or, for example, the family house in Dobřejovice near Prague by architects Poláček and Škarda, whose sloping roof recalls the lean-tos around the yards of village homes. The house by Markéta Cajthamlová in Počernice near Prague is based on the foundations of a vanished farm, replicating its proportions and layout, yet its style is more influenced by the traditions of modern European regionalism than by Czech village vernacular.

A special attempt at rural architecture is the family house in Hodonín by Zdeněk Fránek. The author here aimed not so much at evoking village buildings but rather at typical objects of village life. To some, the house may recall a jug; Fránek himself speaks directly of a bag.

But why should we only be inspired by old village buildings when searching for vernacular? The typical image of the Czech countryside also comprises much younger structures. I mean the so-called steel barns that have spread across the rural landscape in the last thirty years almost to the same extent as panel houses in cities. I would not be far off in saying that the model for Hrůša's and Pelčák's tennis club on the outskirts of Litomyšl was such a steel barn.

The second path to achieving a regional Czech vernacular involves imitating cabins and summer houses. I repeat, you will not find as many wooden cottages anywhere else in Europe as here. When Svatopluk Sládeček and Luděk del Maschio designed the municipal office in the village of Šarovy near Zlín, they evidently followed the language of cabins. Something similar applies to Sládeček's family house in Rajhrad near Brno or the wooden buildings of Kopřivnice architect Kamil Mrva.

Figures and Barbarians

At Sládeček, I must digress. I find it important that some of his houses are labeled as figurative. American postmodernists, such as Michael Graves, wrote about figurative architecture, suggesting that a building benefits from reminding us of some animal or object. The small house in Rajhrad is referred to by Sládeček as "television" or "screen," and soon we will see "a gopher" from him. But I am interested in the ironic diminutive—"figurkativity" instead of "figurativity." I believe that Sváťa touches on something deeply Czech here, something that transcends the realm of architecture: typically Czech human types, typically non-heroic, non-gallant, as depicted in the prose of Neruda, Hašek, or Hrabal. Perhaps it is from here, from "Tales from the Lesser Town" or from Švejk, that the path to Czech regionalism can lead.

The question of something typically Czech was also posed by David Kraus, the author of the wooden family house in Říčany near Prague. He pondered how Czech culture differs from Western culture and concluded that it lies in the degree of cultivation. We Czechs, nor Czech architects, will never reach Western cultivation. Therefore, we have no choice but to cultivate our Czech barbarism and turn it into a positive.

Czech Sun

If we want to know what is specific to Czech or Central European architectural tradition, it pays to ask foreigners, foreign architects, and architecture historians about it. We ourselves are too embedded in our environment and do not have sufficient distance from it. I once read an interview with Norwegian architecture historian Christian Norberg-Schulz, the author of the book Genius loci, and I also heard what Frank Gehry says about Central European or directly Prague architecture. They both agreed that Czech or Central European architecture has almost always been characterized by being plastered and that its creators could play gently with light and shadows on plastered facades.

I believe that Josef Pleskot utilized the same insight during the renovation of the town hall in Benešov. At the back wing, he played with the varying depths of the façade openings, dark at the arcade and lighter in the upper floors. The top floor of the town hall facing the square then curves back to create a gentle arc in the shadow.

Back to Techniques: Walls, Paving

Pleskot, like Lábus or Jan Línek, readily admits that part of his work has a regionalist character. In Línek's case, we could even trace the inspiration of rural architecture, which I have already mentioned. The irregular layout of the residential farm in Kostelec nad Černými lesy was traced by Línek from one farm in Strakonice, whose images he found in Václav Mencl's book Czech Folk Architecture. But now I will be interested in the carefully arranged stone walls that Línek encircled the garden of the Kostelec farm with.

I said that famous Western regionalists are half architects and half landscapists, and they are interested in the ways people have transformed the landscape over the centuries. Snozzi incorporates ancient terraces at the foothills of the Swiss Alps into his buildings; the Venetian Scarpa liked to use water channels and ditches.

One such ancient way of transforming the landscape can also be found in our country. If you look at old maps of Czech towns and villages, you will find that thin, long plots or gardens extend from every house. Such plots have historically been separated from each other by stone walls.

A remnant of such a wall also stood behind the residential farm in Kostelec nad Černými lesy. Línek had it carefully restored because he considered it important for his concept. There is nothing regionalist about the houses with starter apartments in Horažďovice designed by Josef Pleskot—except for the careful reconstruction of the stone wall that delineates its plot. Pleskot also equipped a villa in Lipence near Zbraslav with a wall, with an upper structure in the spirit of cabin vernacular on a vast flat roof.

Sometimes an architect's intervention may be limited to the wall itself, bypassing the roof. For such a landscape treatment rather than purely architectural improvement, Zdenka Vydrová is indebted for the sub-mansion in Litomyšl, a connecting path between the parking lot and the castle, which the architect surrounded with walls and carefully paved. I generally believe that very typical regionalist tasks include the improvement of public spaces, such as the one demonstrated by Petr Hrůša and Petr Pelčák in the park under the Petrov hill in Brno. Finally, paving can also be considered a product of regionalism, especially when it seeks to achieve a traditional and time-non-specific appearance. In Hana Zachová's pavements in Český Krumlov, we cannot be sure when they were actually created, and thus they resonate regionally, while the paving in the courtyard of the Archdiocesan Museum in Olomouc by the team of Hájek-Hradečný-Šépka does not disguise its authors’ fondness for modern abstract art and does not belong within the framework of regionalism.

Citing Regionalism from Abroad

The techniques of Czech regionalism are not sufficiently developed yet. Even those architects who are not afraid of identifying with this trend often do not know how to express their regionalist ambition well. It is not surprising, therefore, that some of them openly cite the works of famous regionalist architects from the West. The family house in Míkovice near Uherské Hradiště is called "gopher" by Svatopluk Sládeček. However, I call it "Alvaro Siza" because it looks like a simplified version of one of the towers in the complex of Siza's Faculty of Architecture in Porto. The details of an excellent regionalist house in Prague-Hlubočepy by Barbora Rossi and Jan Mrázek remind us of the works of Italian representatives of this trend, such as Scarpa's adaptation of the Tolentini Monastery in Venice or the house of Gino Zucchi on the Venetian island of Giudecca.

Conclusion

I do not believe that regionalism should be the only path of contemporary architecture. It can comfortably remain on the periphery. However, there are reasons that justify its survival, and thus regionalist creation will not disappear from the scene in our country either. Primarily, I mean the resistance to globalized architecture.

Looking at the Hlubočepy house by the Rossi-Mrázek team, another undeniable quality of regionalist architecture comes to mind, especially important for Czech lands with such a high number of preserved historical settlements. Regionalist buildings simply fit well into historical contexts. Although this trend does not offer a single correct method for how contemporary architecture should enter a historic city, it provides a guarantee that you will not make a major mistake in the process.

|

a professional architectural bimonthly

Era 21 has earned a reputation as a quality professional magazine during its five-year existence, with each issue thematically elaborated. The careful selection of profile topics that also open discussions on issues that have previously remained in "professional ignorance" has contributed to the very positive reader response.

> table of contents of issue 3/2006

> subscription order

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.