Ladislav Žák: K. Teige - The Smallest Apartment

The extensive book, which was recently published by the Václav Pter Publishing House, is not, as one might assume from the title, a guide instructing how to furnish an apartment or build a house. At a time when we are already inundated with professional and popular books of various values and levels discussing the topic of housing, today, when every daily and illustrated publication has its housing section, where phrases about functional, simple, and tasteful apartment solutions are parroted and diluted to the point of exhaustion—these phrases hammered into the minds of the public by authors who, until recently and to this day, are far removed from modern architectural thinking—it would indeed mean, as the author states in the preface to his book, to carry coals to Newcastle if his book, The Smallest Apartment, were merely another practical guide of this kind.

The book The Smallest Apartment is the work of a sociologist. It is the first major work in Czech professional literature in which all questions of housing are considered from the standpoint of economic and social development. This viewpoint gives the book a firm internal coherence. The critique of all previous results and attempts to solve the housing question, as well as the prognosis of future forms of housing, is based on the method of dialectical materialism, according to which the housing question is rightly positioned as a mere, albeit very important, component of the overall struggle for a new social and economic form. The Smallest Apartment is not a popular book; its purpose, as the author has determined, is scientific collaboration with the International Congresses of Modern Architecture and their executive committee (CIRPAC), which identified the problem of the smallest apartment as a central problem of modern architecture, solvable only through close collaboration between sociology, economics, medical sciences, politics, and law. — If Czechoslovakia has occupied a significant position at the International Congresses of Modern Architecture, it should be emphasized that this success was largely achieved precisely through the sociologically clarified and consistent standpoint formulated by Karel Teige in the congress publication Rationelle Bebauungsweisen in the section: The Housing Question of the Existence Minimum Classes. The Smallest Apartment, as an extensive scientific book, is thus primarily intended for professionals. It would be desirable for the large group of architects who are or want to be considered modern to devote careful attention to this work, which is also an excellent textbook for students of all architectural universities. Furthermore, the book The Smallest Apartment should find expansion among modern sociologists, national economists, doctors, and all cultural workers to whom the solution of the housing question directly or indirectly pertains. Should, due to the influence of Teige's book, a realization finally occur within the large group of modern architects, many of whom still do not understand that technical progress is merely a natural component of modern architectural thought, which absolutely inseparably requires a new social order for its practical full development — then the purpose of the book will be fulfilled. Another consequence will be the gradual influence of aware professionals on practice. To this delicate point, it is crucial to realize that we are dealing today with a developmental turning point of a far deeper content and far broader scope than at any moment in previous developmental periods. Just as the world has changed technologically in the last hundred years due to science and industry more than in all the previous millennia — as there is a fundamental difference between historical and new architecture, so a turning point is occurring in social development that will likely change the social and economic structure of the world more than it has changed in all previous historical periods. Modern architecture, which shortly after the war assumed a solid form through the current work of leading experts in various places in the world and Europe, is internally more coherent than the styles of historical periods, emerging initially as a new technical and aesthetic system conceived within the framework of the existing social order. — However, soon the internal connection and mutual dependence between new architecture and a new economy became apparent; the same chasm between the immense possibilities of production and the astonishing backwardness of distribution, recently revealed by technocrats in America, also opens up between the magnificent plans of modern architecture and the current ancient system of dispersed small builders. Just as American technocrats have come to the conviction of the necessity of changing the ancient distribution system, which continually excludes greater masses from the possibility of consuming giant production, so must the modern architect, even if he knows nothing about new political opinions and efforts, logically conclude that the precondition for the development of the untapped possibilities of new architecture in all its fields, especially in housing, is the victory of a new social system.

If the change in orientation from decorative "national" architecture, which was popular after the war, to new puristic house designs required a rather superficial and hence somewhat superficial transformation from architects and the public, the current developmental situation requires a much deeper change in perspective: it is necessary for the entire human mentality and ideology to fundamentally change. — For these seeds not to be superficial, they must be prepared very seriously and thoroughly. Entire brigades of aware cultural workers should be mobilized to prepare for the victory of that segment of culture, which is new housing. Propagating and creating a new ideology is not just the task of architects; modern sociologists, national economists, hygienists, doctors, and other cultural workers should systematically raise awareness among increasingly wider circles of the population about the necessity of new cultural forms, just as progressive politicians prepare new political forms correlating with new cultural forms.

Now let’s look at the content of the book The Smallest Apartment. — In the introductory notes on the dialectic of architecture and the sociology of housing forms, the author rightly declares the housing question to be a problem of statistics and technique, part of a general plan to address both the material and cultural needs of the population. This clarifies the necessity of judging the housing question through the lens of Marxist sociology. — The paragraph where the tasks of the architectural avant-garde are formulated deserves a separate reflection, which could be titled "Architecture as Science vs. Architecture as Trade." The relationships between architectural theory and practice during this transitional period will need to be carefully considered and formulated. — In the following paragraphs, the social characteristics of the original primitive apartment, the current apartment of the ruling class, and the proletarian apartment are analyzed, from which the future form of the collective dwelling of a classless society emerges as a contradiction. This outline is detailed in the individual chapters, forming the entire content of the book.

In the paragraph on housing scarcity, it is shown that this scarcity only pertains to the proletariat and proletarianized middle classes of the impoverished intelligentsia: there is no shortage of apartments, but rather a shortage of cheap apartments; in other words, the wage level of the working population is so low that these layers cannot be consumers of housing speculation. — There is also no excess population; overpopulation is relative, as it corresponds to overproduction in industry and agriculture. The existential minimum for the broadest layers today is not a "minimum vivendi" (the minimum with which one can live), but rather a "minimum non moriendi" (the minimum with which one does not die of hunger). — It is not possible to build even the smallest apartments for the most impoverished, as rent in the smallest apartments would exceed their payment capacity. Even less can the housing scarcity of the proletariat be resolved by constructing mass-produced family homes, which in fact act as an opiate that undermines the struggle for a new social order. The housing of the proletariat amounts only to lodging. The accumulation of many lodgers in filthy dens of rented barracks causes a high mortality rate from tuberculosis, which cannot be eliminated by the construction of expensive mountain sanatoria.

In the section "International Deficit of the Housing Question," housing care in European states is analyzed, showing how the efforts to alleviate housing scarcity are either misguided or even fraudulent, how even the greatest activity in this regard (Vienna, Frankfurt) ultimately did not lead to results, as it always failed due to a financial system whose conditions make solving housing scarcity impossible. —

In the USSR, despite the nationalization of housing property and generous construction of entire cities, housing distress still persists. — In Czechoslovakia, there have not been even attempts to solve the housing problems of the poorest layers. —

In the subsequent paragraphs, the historical development of cities, the fact of capitalist metropolises, and the contradiction between city and countryside is clarified, which, as Marx wrote, "transforms one person into a limited urbanite, another person into a limited rural animal." — The development of historical and modern cities, "regulated" by so-called regulatory and construction regulations, shows that these regulations always yield to the private capitalist and exploitative tendency, which displaces the population from the center, creating business cities, accumulating the proletariat in neglected, poorly situated districts, displacing greenery and recreational areas in the interest of maximum profit. —

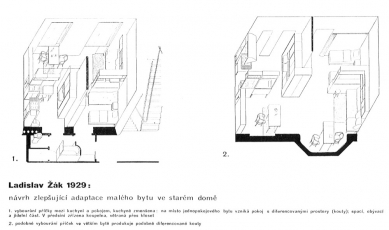

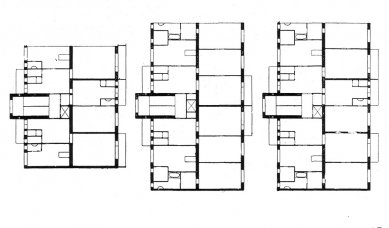

In American cities, skyscrapers clustered in the business center increase the density of the population to a dangerous degree and thereby cause the most serious transport disruptions. The unorganized relationship between residences and workplaces exacerbates transport difficulties, forcing massive daily population shifts resembling daily migrations, resulting in the loss of enormous amounts of time in transit, which is neither rest nor recreation, nor productive activity. The problem of transport and housing is closely related. A solution is possible only by overcoming production anarchy and the victory of genuine public interests over private interests. — The remedy of English garden cities does not solve the situation; working in the city or at the opposite end and living in the outskirts in garden suburbs is a romantic delusion. Instead of 8 hours of work, 8 hours of recreation, and 8 hours of sleep, the result instead is 8 hours of work, 7 hours of lost time in transit, 3 hours of private life, and 6 hours of sleep. — Le Corbusier's projects for metropolises are utopian mainly because they assume grand foundational acts within the framework of the capitalist economy, which is characterized by an inability for large planned endeavors and rather by natural random growth, albeit powerful, but disorganized and uncontrollable. Furthermore, the question of the countryside is completely unaddressed in these projects. Another fallacy is sociological: the construction of housing for broad layers is merely a natural component of the new social order, yet Le Corbusier believes that constructing housing can prevent the arrival of a new social form. — Since the bacillus of the chronic illness of contemporary cities is the capitalist system itself, any treatment within its framework is symptomatic treatment, not a remedy for the disease. Neither the dissolution and abolition of cities and a return to the countryside, nor the removal of the countryside and concentrating the entire population in cities will likely be the correct resolution. New technical advancements (electricity, radio, cinemas, television, and unpredictable new inventions) will allow for an even distribution of humanity, which Lenin foresaw. Desurbanization, socialist reconstruction, and ultimately the obsolescence of old cities, the building of new formations that are neither cities nor villages, are, however, more likely to resemble today’s idea of a city (strip cities, socgordies, socialist housing developments in the USSR), indicating the beginning of a solution, the later forms of which are hardly predictable today, since rapid technical development is incalculable. In the chapter "Housing and Household of the 19th Century," it is shown how both main today’s residential building forms have a class character. The apartment building, a "machine for profit" for the owner, a coffin for tenants. The family house, luxury and representation for property classes, an opiate for the proletariat. The family apartment and household in both these forms is, from the standpoint of economic work and division of labor, an underdeveloped form. Wealthy families require a staff to maintain the operation of the large house, in poor families, the homemaker is exploited either through dual work (productive and domestic) or dehumanized and enslaved by the outdated method of managing the household, cumbersome in its operation, or finally, in a rationalized household, the man is exploited, as the small household does not employ women in a way equivalent to a man’s intensive work. The inconsistencies that arise here are the cause of frequent breakdowns of bourgeois marriages; the family life of the proletariat has long been shattered and made impossible by the employment of men, women, and children. — Running a household today is a nonsensical ancient waste of energy, amateurism, which hinders the inclusion of women in production in both material and intellectual work and thus their ultimate equalization. Despite the calculations and critiques of exemplary settlements and housing projects with which new architecture promoted new housing after the war, despite the explanations about the layout forms of modern apartments and houses (the content of these chapters suggests K. Teige’s article in issue 8 of "We Live": "Three Types of Small Apartments"), despite the explanation of building systems and regulations, the author arrives at the chapter on new forms of housing. He shows how the proletariat, deprived of the ability to have a household (men, women, and children employed in production, the family as a social entity destroyed), through logical development adopts the most advanced form of housing and life management created by the capitalist system, the hotel form, and from this foundation creates a new, higher way of living and cultural life, collective cities, districts, and houses, in which every adult resident is entitled to a small private living room, well-furnished, and the right to use collective recreational, cultural, and social facilities. — The author correctly clarifies here how precisely from the sad fact of the destruction of the proletarian family arises a new and developmentally superior form, which will allow for an unexpected development of the individual, the deepening and clarification of the relationship between man and woman, who will be freed from the slavery and inequality caused by today’s backward barbaric forms of households and family apartments.

After depicting concrete attempts and theoretical opinions and projects of Soviet experts, having first evaluated foreign as well as our laboratory projects for new housing, Karel Teige concludes his book with a beautiful reflection on the arrival of a new form of housing: "Today? Tomorrow?" — "It is certainly not possible to predict with detail the lifestyles and conditions of the distant future; it would be utopian to want to prophesy concrete forms of life in an era of developed socialism... What we have stated about collective living is, as we believe, not a utopia, but a hypothesis about architectural tomorrows, about the future of housing culture and urbanism, and a call to fight for tomorrow. A hypothesis validated by the historical probability count, which is dialectical materialism, Marxism."

The book The Smallest Apartment is the work of a sociologist. It is the first major work in Czech professional literature in which all questions of housing are considered from the standpoint of economic and social development. This viewpoint gives the book a firm internal coherence. The critique of all previous results and attempts to solve the housing question, as well as the prognosis of future forms of housing, is based on the method of dialectical materialism, according to which the housing question is rightly positioned as a mere, albeit very important, component of the overall struggle for a new social and economic form. The Smallest Apartment is not a popular book; its purpose, as the author has determined, is scientific collaboration with the International Congresses of Modern Architecture and their executive committee (CIRPAC), which identified the problem of the smallest apartment as a central problem of modern architecture, solvable only through close collaboration between sociology, economics, medical sciences, politics, and law. — If Czechoslovakia has occupied a significant position at the International Congresses of Modern Architecture, it should be emphasized that this success was largely achieved precisely through the sociologically clarified and consistent standpoint formulated by Karel Teige in the congress publication Rationelle Bebauungsweisen in the section: The Housing Question of the Existence Minimum Classes. The Smallest Apartment, as an extensive scientific book, is thus primarily intended for professionals. It would be desirable for the large group of architects who are or want to be considered modern to devote careful attention to this work, which is also an excellent textbook for students of all architectural universities. Furthermore, the book The Smallest Apartment should find expansion among modern sociologists, national economists, doctors, and all cultural workers to whom the solution of the housing question directly or indirectly pertains. Should, due to the influence of Teige's book, a realization finally occur within the large group of modern architects, many of whom still do not understand that technical progress is merely a natural component of modern architectural thought, which absolutely inseparably requires a new social order for its practical full development — then the purpose of the book will be fulfilled. Another consequence will be the gradual influence of aware professionals on practice. To this delicate point, it is crucial to realize that we are dealing today with a developmental turning point of a far deeper content and far broader scope than at any moment in previous developmental periods. Just as the world has changed technologically in the last hundred years due to science and industry more than in all the previous millennia — as there is a fundamental difference between historical and new architecture, so a turning point is occurring in social development that will likely change the social and economic structure of the world more than it has changed in all previous historical periods. Modern architecture, which shortly after the war assumed a solid form through the current work of leading experts in various places in the world and Europe, is internally more coherent than the styles of historical periods, emerging initially as a new technical and aesthetic system conceived within the framework of the existing social order. — However, soon the internal connection and mutual dependence between new architecture and a new economy became apparent; the same chasm between the immense possibilities of production and the astonishing backwardness of distribution, recently revealed by technocrats in America, also opens up between the magnificent plans of modern architecture and the current ancient system of dispersed small builders. Just as American technocrats have come to the conviction of the necessity of changing the ancient distribution system, which continually excludes greater masses from the possibility of consuming giant production, so must the modern architect, even if he knows nothing about new political opinions and efforts, logically conclude that the precondition for the development of the untapped possibilities of new architecture in all its fields, especially in housing, is the victory of a new social system.

If the change in orientation from decorative "national" architecture, which was popular after the war, to new puristic house designs required a rather superficial and hence somewhat superficial transformation from architects and the public, the current developmental situation requires a much deeper change in perspective: it is necessary for the entire human mentality and ideology to fundamentally change. — For these seeds not to be superficial, they must be prepared very seriously and thoroughly. Entire brigades of aware cultural workers should be mobilized to prepare for the victory of that segment of culture, which is new housing. Propagating and creating a new ideology is not just the task of architects; modern sociologists, national economists, hygienists, doctors, and other cultural workers should systematically raise awareness among increasingly wider circles of the population about the necessity of new cultural forms, just as progressive politicians prepare new political forms correlating with new cultural forms.

Now let’s look at the content of the book The Smallest Apartment. — In the introductory notes on the dialectic of architecture and the sociology of housing forms, the author rightly declares the housing question to be a problem of statistics and technique, part of a general plan to address both the material and cultural needs of the population. This clarifies the necessity of judging the housing question through the lens of Marxist sociology. — The paragraph where the tasks of the architectural avant-garde are formulated deserves a separate reflection, which could be titled "Architecture as Science vs. Architecture as Trade." The relationships between architectural theory and practice during this transitional period will need to be carefully considered and formulated. — In the following paragraphs, the social characteristics of the original primitive apartment, the current apartment of the ruling class, and the proletarian apartment are analyzed, from which the future form of the collective dwelling of a classless society emerges as a contradiction. This outline is detailed in the individual chapters, forming the entire content of the book.

In the paragraph on housing scarcity, it is shown that this scarcity only pertains to the proletariat and proletarianized middle classes of the impoverished intelligentsia: there is no shortage of apartments, but rather a shortage of cheap apartments; in other words, the wage level of the working population is so low that these layers cannot be consumers of housing speculation. — There is also no excess population; overpopulation is relative, as it corresponds to overproduction in industry and agriculture. The existential minimum for the broadest layers today is not a "minimum vivendi" (the minimum with which one can live), but rather a "minimum non moriendi" (the minimum with which one does not die of hunger). — It is not possible to build even the smallest apartments for the most impoverished, as rent in the smallest apartments would exceed their payment capacity. Even less can the housing scarcity of the proletariat be resolved by constructing mass-produced family homes, which in fact act as an opiate that undermines the struggle for a new social order. The housing of the proletariat amounts only to lodging. The accumulation of many lodgers in filthy dens of rented barracks causes a high mortality rate from tuberculosis, which cannot be eliminated by the construction of expensive mountain sanatoria.

In the section "International Deficit of the Housing Question," housing care in European states is analyzed, showing how the efforts to alleviate housing scarcity are either misguided or even fraudulent, how even the greatest activity in this regard (Vienna, Frankfurt) ultimately did not lead to results, as it always failed due to a financial system whose conditions make solving housing scarcity impossible. —

In the USSR, despite the nationalization of housing property and generous construction of entire cities, housing distress still persists. — In Czechoslovakia, there have not been even attempts to solve the housing problems of the poorest layers. —

In the subsequent paragraphs, the historical development of cities, the fact of capitalist metropolises, and the contradiction between city and countryside is clarified, which, as Marx wrote, "transforms one person into a limited urbanite, another person into a limited rural animal." — The development of historical and modern cities, "regulated" by so-called regulatory and construction regulations, shows that these regulations always yield to the private capitalist and exploitative tendency, which displaces the population from the center, creating business cities, accumulating the proletariat in neglected, poorly situated districts, displacing greenery and recreational areas in the interest of maximum profit. —

In American cities, skyscrapers clustered in the business center increase the density of the population to a dangerous degree and thereby cause the most serious transport disruptions. The unorganized relationship between residences and workplaces exacerbates transport difficulties, forcing massive daily population shifts resembling daily migrations, resulting in the loss of enormous amounts of time in transit, which is neither rest nor recreation, nor productive activity. The problem of transport and housing is closely related. A solution is possible only by overcoming production anarchy and the victory of genuine public interests over private interests. — The remedy of English garden cities does not solve the situation; working in the city or at the opposite end and living in the outskirts in garden suburbs is a romantic delusion. Instead of 8 hours of work, 8 hours of recreation, and 8 hours of sleep, the result instead is 8 hours of work, 7 hours of lost time in transit, 3 hours of private life, and 6 hours of sleep. — Le Corbusier's projects for metropolises are utopian mainly because they assume grand foundational acts within the framework of the capitalist economy, which is characterized by an inability for large planned endeavors and rather by natural random growth, albeit powerful, but disorganized and uncontrollable. Furthermore, the question of the countryside is completely unaddressed in these projects. Another fallacy is sociological: the construction of housing for broad layers is merely a natural component of the new social order, yet Le Corbusier believes that constructing housing can prevent the arrival of a new social form. — Since the bacillus of the chronic illness of contemporary cities is the capitalist system itself, any treatment within its framework is symptomatic treatment, not a remedy for the disease. Neither the dissolution and abolition of cities and a return to the countryside, nor the removal of the countryside and concentrating the entire population in cities will likely be the correct resolution. New technical advancements (electricity, radio, cinemas, television, and unpredictable new inventions) will allow for an even distribution of humanity, which Lenin foresaw. Desurbanization, socialist reconstruction, and ultimately the obsolescence of old cities, the building of new formations that are neither cities nor villages, are, however, more likely to resemble today’s idea of a city (strip cities, socgordies, socialist housing developments in the USSR), indicating the beginning of a solution, the later forms of which are hardly predictable today, since rapid technical development is incalculable. In the chapter "Housing and Household of the 19th Century," it is shown how both main today’s residential building forms have a class character. The apartment building, a "machine for profit" for the owner, a coffin for tenants. The family house, luxury and representation for property classes, an opiate for the proletariat. The family apartment and household in both these forms is, from the standpoint of economic work and division of labor, an underdeveloped form. Wealthy families require a staff to maintain the operation of the large house, in poor families, the homemaker is exploited either through dual work (productive and domestic) or dehumanized and enslaved by the outdated method of managing the household, cumbersome in its operation, or finally, in a rationalized household, the man is exploited, as the small household does not employ women in a way equivalent to a man’s intensive work. The inconsistencies that arise here are the cause of frequent breakdowns of bourgeois marriages; the family life of the proletariat has long been shattered and made impossible by the employment of men, women, and children. — Running a household today is a nonsensical ancient waste of energy, amateurism, which hinders the inclusion of women in production in both material and intellectual work and thus their ultimate equalization. Despite the calculations and critiques of exemplary settlements and housing projects with which new architecture promoted new housing after the war, despite the explanations about the layout forms of modern apartments and houses (the content of these chapters suggests K. Teige’s article in issue 8 of "We Live": "Three Types of Small Apartments"), despite the explanation of building systems and regulations, the author arrives at the chapter on new forms of housing. He shows how the proletariat, deprived of the ability to have a household (men, women, and children employed in production, the family as a social entity destroyed), through logical development adopts the most advanced form of housing and life management created by the capitalist system, the hotel form, and from this foundation creates a new, higher way of living and cultural life, collective cities, districts, and houses, in which every adult resident is entitled to a small private living room, well-furnished, and the right to use collective recreational, cultural, and social facilities. — The author correctly clarifies here how precisely from the sad fact of the destruction of the proletarian family arises a new and developmentally superior form, which will allow for an unexpected development of the individual, the deepening and clarification of the relationship between man and woman, who will be freed from the slavery and inequality caused by today’s backward barbaric forms of households and family apartments.

After depicting concrete attempts and theoretical opinions and projects of Soviet experts, having first evaluated foreign as well as our laboratory projects for new housing, Karel Teige concludes his book with a beautiful reflection on the arrival of a new form of housing: "Today? Tomorrow?" — "It is certainly not possible to predict with detail the lifestyles and conditions of the distant future; it would be utopian to want to prophesy concrete forms of life in an era of developed socialism... What we have stated about collective living is, as we believe, not a utopia, but a hypothesis about architectural tomorrows, about the future of housing culture and urbanism, and a call to fight for tomorrow. A hypothesis validated by the historical probability count, which is dialectical materialism, Marxism."

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment