Prague will grow in height

Post by Jiří Ploš to the thematic evening Architect versus History

Contribution by Jiří Plos

Contribution by Richard Biegel

The topic of this discussion is the relationship of new construction (including high-rise buildings) in Prague to heritage protection - more generally, to history. It is not just about high-rise buildings, but a holistic approach to the urban development of the city. High-rise buildings represent only one possible segment or manifestation of construction. The requirements of heritage protection represent yet another narrowing of this subset: however, they pose certain questions whose answers have significant consequences for the development of the city. Among these questions, in relation to the height of buildings, it primarily concerns whether, and if so, whether the construction development of Prague can be terminated in any part of it. Whether the development of the skyline of Prague can be terminated at all. Whether the development of the height of construction can be terminated, or its height "level".

|

MISSING CONCEPT

|

HERITAGE PROTECTION AS A BRAKE?

Heritage protection is, of course, a historically conditioned phenomenon, and its essence is a social contract - an agreement. The view of heritage protection is variable; many formerly condemned urban and architectural endeavors (among many others Baroque, Art Nouveau, Functionalism) are gradually taken into consideration and subsequently become the subject of its interest, that is, in the best case care, in the worst case protection! This public interest can vary in different parts of the city, but it never stands alone. Alongside this public interest, there are not only private interests (consistently very diverse, and therefore often mutually contradictory), but also other public interests, for which the same applies. The interest of heritage protection differs from the interest of nature and landscape protection, differs from the interest of fire safety, hygiene, or infrastructure. In formulating its requirements, heritage protection must primarily draw from the facts and findings typical and characteristic for it, conditioned by the field. However, it cannot ignore other interests and the broader interrelations among them. Without the ability to weigh the intensity of the protected interest, to hierarchize it and sufficiently qualify and specify it - heritage protection becomes rather a brake on the emergence of new authentic layers of urban and architectural character, which in turn goes against its own interests in future heritage protection.

|

INSUFFICIENT DEFINITION

The fundamental problems concerning contemporary heritage protection in relation to Prague's urban development are found in the following:

- on the one hand, the insufficient specific definition of care conditions (not only protection, but even that!) in the historical environment itself (e.g., PPR),

- on the other hand, the completely inadequate definition of conditions in protective zones (the protective zone of PPR is a typical example) and decision-making conditions.

|

None of us doubt that different parts of the city are rated differently in various perspectives. None of us will probably question the importance of caring for preserved evidence of the cultural-civilizational development of the city. However, this cannot be equated only with some sort of nostalgia, to which any expressions of current (and future-predicting) urban and architectural development are alien, incomprehensible, and fundamentally hostile. Which not only does not understand but - and this is much more serious - fundamentally does not want to understand! None of us will doubt the importance of individual cultural-civilizational layers; nevertheless, in specific decisions, the same reservations repeatedly appear, which defend new expressions citing some kind of closure. This usually hides behind the guise of not entirely clarified and consistent notions, such as authenticity, identity, and so on. Nevertheless, is not contemporary urbanism, is not contemporary architecture a manifestation of a profoundly authentic character?

THE RIGHT TO A NEW LAYER

If the interest of heritage protection is to be generally respected, then it must be formulated, justified, and relate only to those facts that are subject to heritage protection. In the case of protected areas, it must allow for the emergence of new urban and architectural layers; in the case of protective zones, it must specify only those conditions that are directly related to the object of care. The specific form of this care, however, must in no case be intended as a prohibition of new construction not only in the protective zone but also in the directly heritage-protected area itself. Although one cannot completely eliminate the influence of personal taste and personality traits, the entire system must not be built on subjective personal taste and opinions that are processually uncorrected and uncorrectable.

|

Jiří Plos

Prague 07. 06. 2007

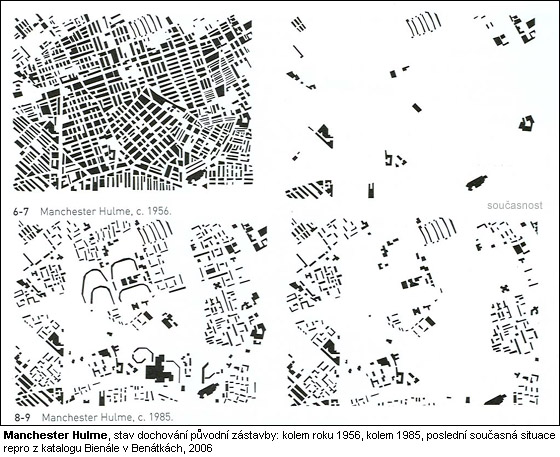

(edited by the editorial office, images accompanied by the editorial office, repro Manchester Hulme taken from the presentation of Jakub Cigler)

|

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment