Sir Neil Cossons: We are all accomplices of globalization

|

The beginnings of industrial archaeology in Britain date back to the late 1950s. Has the British government's approach to industrial heritage changed during your professional career?

Just for illustration, in 1913, one hundred two hundred thousand men were involved in coal mining in Britain, there were 3,100 coal mines; today there are 6 mines and 5,600 people work in them… Even in the 1940s, Labour Minister Aneurin Bevan spoke of Britain as a country of a future industrial nation, an "island of coal surrounded by a sea of fish." Today we have no coal and no fish. Even at the time when my interest in industrial archaeology was being born, Britain proudly built new railways, invested in nuclear energy, or constructed Concords. Today, manufacturing contributes only 15 percent of Britain's gross domestic product. By the way, in China, it is 37 percent and the figure is still rising...

Over the past forty years, there has been an awareness that this era represented a very fundamental period in our history and recognizing values is also the beginning of more serious investments in this area.

If you are asking about the current government's attitude towards industrial heritage, the cabinet primarily has the role of influencing legislation. The concept for successful functioning confirms the necessity for intensive cooperation between the private and public sectors. From the financial motivation perspective, the current cabinet treats industrial monuments primarily as a means to increase tourism. Another significance of the cabinet in this regard stems from the awareness that the government is an entity that can shift and also shifts public opinion. The current problem, in my view, remains that the British cabinet has never clearly defined what it considers an optimal social investment in industrial heritage.

|

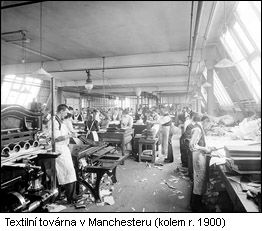

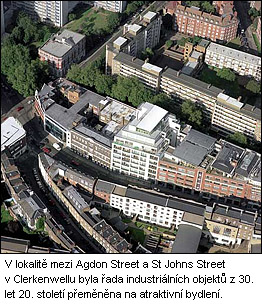

Fortunately, most of them allow for new purposes. Primarily factories. We conducted a survey of textile factories in the Manchester area. There are over a thousand empty here! Some, of course, have been demolished, but all significant ones are today being converted into offices, apartments, and in some cases even for new light industries, such as electronics.

On your side, there is also an awareness that assigning new uses to buildings is part of the natural rhythm of a house's life...

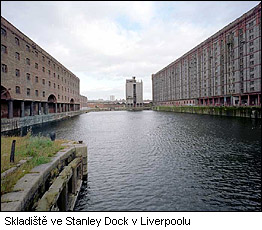

With the industrial ones, the problem is that their original purpose disappeared practically all at once. We have hundreds of them. All of a sudden. And the economy is not strong enough to support them all. It is, therefore, impressive to observe how large industrial cities like Liverpool, Manchester, or Leeds are beginning to see these objects as assets rather than liabilities. What was previously regarded as a problem is now seen as an opportunity.

However, there must also be opponents of conversions and investments in industrial heritage in general. Or am I mistaken?

Monetarists. They would say: Forget Liverpool. Let it sink! People will move, and we will invest in the southeast, in the part closest to continental Europe, which is currently booming. Here we have a chance for a return on investment. However, politically, it is impossible: after all, the residents of Liverpool have voting power. Not long ago, for example, the government believed there was a surplus of housing in northern England due to the collapse of industry. And therefore, it implemented a policy aimed at demolishing old industrial colonies and investing in the south, where people needed apartments. However, this strategy had a short lifespan. It heavily reflected in voting preferences. Moreover, the locals had nowhere to go. And they wanted to stay in the north. Today, no government would agree with monetarists.

|

The government strategy recognized that using these lands would prevent them from lying fallow. But primarily, there is already established engineering and social infrastructure: that is, transportation, short distance to work, etc. And the third reason, of course, is urban awareness: that if we do not continue to develop the countryside, we will eventually have none left.

However, you mentioned the absence of a government framework for investments in social strategy...

Support aims to keep people in troubled areas. We no longer manufacture and export railway locomotives: like most European countries, we are primarily a service economy today, selling financial services, creativity, films. And you can do that from anywhere. Geography is no longer a limit. Manchester, for example, has built a leading financial sector. Similarly Leeds. But for that to happen, initial government incentives were necessary.

However, as a result of earlier mistakes, we now, according to statistics in comparison to most European countries, have the longest average commute. We do not have enough housing in the city center, and if it exists, it is expensive. People are therefore moving farther out for cheaper homes and commuting up to 150 km daily in every direction.

This issue is very closely related to ecology...

Undoubtedly. It is alarming resource waste. The influence of ecology, however, is fortunately becoming stronger. If you live outside the city, the road infrastructure is completely overloaded. And we all know that if we build more roads, we will always have more cars. The same goes for the railway. In Britain, the number of railway passengers increases by 7-8 percent annually. A good trend in the last twenty years is, let’s say, that the original out-migration from cities to the countryside, which was typical of the last century, is now reversing: people want to live in city centers for the possibility of social activities, in good apartments.

|

Abandoned industrial buildings in the centers are perceived as modern. Especially for young professionals, with higher incomes, often childless, they are very attractive. Later, when they start looking for schools for their children, they often move to the suburbs…

???

Unfortunately, we have almost no schools in the centers anymore. Although new ones are being built today. We are therefore watching a revival of city life, or in Roger's terms, an "urban renaissance," resulting from investments in brownfields.

In addition to overloaded infrastructure, the second reason for "social investing" is the protection of the countryside, which we traditionally love in Britain. By the way, English Heritage has conducted public surveys in various regions. And we found that more than 80 percent of respondents consider heritage very important.

Is this also true for industrial communities?

Certainly. Although they were linked to factories that often provided grim working conditions, post-industrial communities highly value this heritage.

I realized this during a visit to the former coal mine in Catlefu,

The locals are proud of the hard work and hardships associated with the place. The history is often paradoxical: when these industrial centers were created, they attracted people from the countryside and were often seen as hostile, hated, proletarian nests.

You have already mentioned that the era of industrial architecture has ended. Does this mean that we no longer build any industrial objects that will need to be protected in the future?

Buildings that will reflect our generation will no longer be factories - because we are no longer really building those - they will be offices, homes, museums…

But factories are certainly being built in Brazil or China. Doesn't that mean, with a dose of exaggeration, that you as a scientist dealing with this type of object should relocate there?

Oh yes. Certainly. In a hundred years. (laughs)

Every country in the world that is not industrial is striving to become one. Whether Brazil, India, or China, they all see industry as an economic force that can lead them from agricultural poverty to some new form of prosperity. With all the social consequences and political instability, as well as the disparities between rich and poor that accompany this endeavor. A social commentator from Manchester in the 1840s would likely have been familiar with the issues of today’s China.

Are today's factories - boxes, prefabricated manufacturing halls - still important for place identity?

I don't know. I really don't know. It takes at least two to three generations for a community to form…

|

In my opinion, opposing globalization is wasting time. Globalization will happen anyway. But you can protect localism and still have globalization. You can live in a small Czech town, and yet have a refrigerator made in Shanghai. And you can afford to buy that refrigerator precisely because it is made in Asia and not in Prague or Stuttgart. The cost of transportation is not decisive. On the contrary, the incredible drop in the price of shipping goods in containers is one of the factors that enables globalization.

Which of course also applies to Britain.

Certainly. Out of loyalty, I have bought British cars all my life. And I still have such a car. But once it falls apart, I won’t be able to buy another: Rover is closed, the brand was bought by the Chinese, and manufacturing has also moved to China.

Or I recently bought a beautiful iron garden bench. The manufacturer was not mentioned.

But you uncovered it...

Among the packaging, I found a note written in small font: Made in China. It cost approximately 250 Czech crowns. And it had been transported halfway around the world. This price must logically cover transportation, the supplier's profit, and the retailer's profit … and one can assume that someone is still making money producing it in China.

And we don’t mind. We like cheap goods, cheap clothes… We are all accomplices in advancing globalization.

So you, former head of English Heritage, are sitting in your garden on a cheap Chinese bench...

Yes. But I also have beautiful garden furniture made of English oak. Which I am proud of and which cost me a lot of money.

And which is more comfortable?

The oak one. (laughs)

Thank you for the interview.

Kateřina Lopatová, Jiří Horský

A shortened version of the interview is published in today’s Hospodářské noviny.

Photos © English Heritage - www.english-heritage.org.uk

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment