|

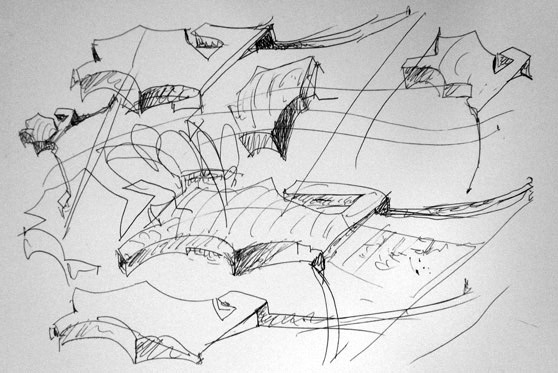

| Sketch by Álvaro Siza for the pavilion in Anyang, South Korea, 2005 |

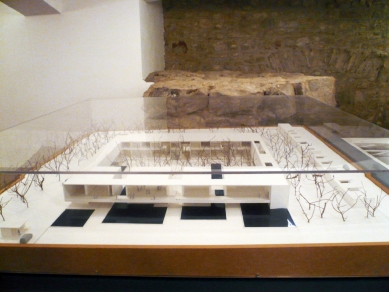

In mid-April, one of the best architectural exhibitions that the Czech capital has had the chance to see in recent years was opened in Prague – both in its form and content. The photographs, plans, texts, and especially the unfortunately not-so-obvious beautiful models for our environment presented projects and buildings whose authors are Portuguese, yet you would search for them in Portugal in vain. The exhibition introduced houses built beyond the borders of their small home country – products of a kind of modern cultural colonization – in the best sense of the word, used here with a degree of exaggeration.

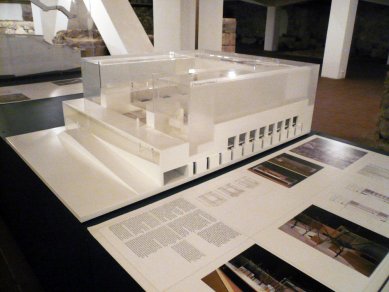

A country whose architectural fame has been confirmed, among others, by Kenneth Frampton, has built its prestige in the recent past primarily on the personality of Álvaro Siza. However, the exhibition curated by architect Ricardo Carvalho with the support of the Portuguese Chamber of Architects showed that the Portuguese scene has significantly expanded since the 1980s. In addition to the Master (whose position, by the way, is not subordinated by the curator), nearly two dozen other offices are also presented: Eduardo Souto de Moura, Inês Lobo and Pedro Domingos, Atelier do Corvo, Gonçalo Byrne, Ricardo Bak Gordon, José Adrião, SAMI Arquitects, Aires Mateus, Carrilho da Graça, Promontório Arquitectos, João Mendes Ribeiro, ARX Portugal, RISCO, Graça Dias and Egas José Vieira, Pedro Reis, Flávio Barbini, and Maria João Silva Barbini.

Locals, who gradually, albeit reluctantly, get used to consuming exhibitions often created hastily and with a limited budget, from which one often catches a glimpse of certain criteria from grant proceedings, could be astonished by the scope of the project and the purity of the concept. The exhibition was taken from the prominent Berlin gallery Aedes, where it was inaugurated a month earlier by the Portuguese president Prof. Dr. Anibal Cavaco Silva.

The encouraging hint that we may indeed be becoming a cultural center of Europe was, however, short-lived – one might say (just like our relatively successful EU presidency). The realization was bitter and the shame great. If you are rightly asking where you can see the showcase of contemporary Portuguese architecture, I reluctantly have to answer: Nowhere. It was originally installed in the lapidary of the Bethlehem Chapel. However, unexpectedly, it was closed a week later. (Counting the evening of the opening and Monday, when the gallery remains closed, it lasted for six days.) I dare say that only a fraction of the professional and student public saw it – especially since its end was announced only for June 4.

The editorial office has not been able to unravel this unusual twist in Czech cultural affairs. A commercially-technical dispute lies somewhere between the six co-organizers and the Administration of Purpose-Built Facilities of the Czech Technical University (which leases the space), and given the indicated character, it does not reflect the quality of the exhibition.

For the viewers, however, the decisive fact is that the exhibition remains closed. Currently, according to available information, no other events are taking place in the lapidary...