It is necessary to focus on cheap and smart energy savings

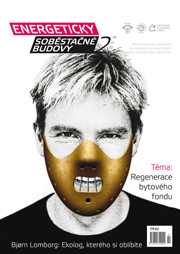

Bjørn Lomborg in the new title Energy Self-Sufficient Buildings

World-renowned Danish ecologist and writer Bjørn Lomborg recently moved to Prague. How does he perceive the domestic capital, efforts for sustainability, and ambitious Danish plans? His first exclusive interview, focused on energy-efficient buildings, construction, and architecture, was presented by the new title Energy Self-Sufficient Buildings (www.esb-magazin.cz), whose editorial staff provided the interview to the readers of the archiweb.

For several months you have been living in Prague. How do you perceive this city and its inhabitants? For several months you have been living in Prague. How do you perceive this city and its inhabitants?I really like it here. I enjoy life in the city, I really like the amazing buildings you have here. I also like the local public transport - I can get to the airport in half an hour, which is important to me. Similarly, I can get anywhere by tram; it would be great if you had it linked to the Google app - it annoys me a bit that I cannot plan the timing of my route through Google. But other than that, it's hard to find anything that I really don't like about Prague. People seem incredibly friendly to me - I speak very little Czech, and the locals are very helpful. When I'm at a loss, I use Google Translate, which often results in bursts of laughter. Do you have any ideas on how we could make the capital more sustainable? In general, we tend to focus on environmental measures that look good, so people focus on them, but these issues actually have very little value. For example, Earth Hour, when the lights were switched off for an hour - everyone felt good about it, but in reality, of course, nothing happened. In my opinion, the main challenge in sustainability today is to sort out and eliminate all the experiments that are done "for good feeling." That is, those that make a person feel environmentally conscious and feel like they are doing good, but these experiments lead to almost no savings at very high costs - for instance, solar panels on inner city walls. While some very simple, old-fashioned, and boring things, such as building insulation, prove to be the greatest benefit. My opinion is: look at how much it costs and what effect it will have. And make sure you are doing things that have great benefits for sustainability, not things that give you a good feeling. Speaking of insulation - there are many historical buildings in Prague that cannot be insulated from the outside, and internal insulation is even more complicated. Utilizing this measure in historic cities can be quite difficult. We must keep in mind that it's not about everyone insulating everything. In connection with insulation in Prague, I would say, don't tackle it in Prague 1. There are tendencies where maximalism becomes the greatest enemy of a good thing. There is often a push to cover everything completely. And if it's not possible, it supposedly makes no sense. But of course it does make sense! Especially if we can do it cheaply and intelligently. So focus on the houses that can be easily insulated. So we should mainly look for energy savings. Yes, but seek the cheap ones. It is extremely important that we do not spend many resources to achieve a tiny bit of good. Do you have any other insights or models that we could apply in Prague? I already mentioned public transport - it is one way to reduce carbon emissions. In Denmark, I did not have a car, and I do not have one in Prague either, yet I can get around quite well. We need to look for intelligent solutions that can significantly reduce carbon emissions at low costs. I used to focus a lot on politics and the global scale, but then I started looking at buildings and found many bad decisions on a small scale. One of my neighbors in Copenhagen installed solar panels on the façade. It doesn’t seem very effective to me - it might be the least efficient solar panel in Denmark, which itself is not suitable for solar panel installation. What lies aheadYou come from Denmark, which has very ambitious sustainability plans. Yet we also hear about the economic crisis in the country. What is the current situation in your country?Denmark has very ambitious goals. It wants to reduce fossil fuel consumption by 80% by 2040; by 2050 it aims to completely operate without fossil fuels. To put it bluntly - I don’t think there is a way to do that. Most of Denmark's ambitions actually consume a huge amount of money, but very little is achieved. For example, in 2012 we heavily subsidized solar panels, which led to a sixfold increase in the number of solar systems sold, and this happened in just one year! When you offer people a really good deal, they will jump at it. And the consequence? Essentially, we will be paying about 300 euros for every ton of CO2 we have avoided over the next twenty years. Yet at present, it is possible to avoid a ton of CO2 for about 5 euros - I simply buy it within the European trading system. So in reality, it is very disadvantageous for Denmark. Germany is even worse off - it pays about 600 euros for every ton of CO2 it saves through solar panels. However, the fact that someone is doing something worse does not mean you should go that way too. When we compare 5 and 300 euros, it means you can reduce emissions sixty times more - and that’s the real crux of the problem. Copenhagen even plans to become a carbon-neutral city. Yes, Copenhagen has decided it wants to be carbon-neutral by 2025, which is in some ways even more absurd - nothing like that will actually happen. The city plans to install wind turbines, which is foolish. Nobody wants wind turbines in their vicinity - they produce very unpleasant infrasound. People do not want them installed in large cities, but rather far from where they live - for example, in the sea. There they would generate more energy and not bother the surrounding area as much. So Copenhagen is set to subsidize a large number of poorly located wind turbines that will bother their surroundings and also import large amounts of biomass from various places. Subsequently, it will show a balanced table to claim it is carbon-neutral. However, if the wind doesn’t blow and the sun doesn’t shine, it will still be importing large amounts of electricity from Sweden, from hydro and nuclear power plants, or from coal plants in other locations in Denmark. Essentially, it’s about someone buying points to boast. So again, it’s about spending a lot of money for a good feeling rather than real reductions in CO2 emissions.

Let's talk about climate change - is it really happening? Is it true? And can humans really be to blame? The answer is yes, yes, and yes again. It exists, it is really happening, and it is partly human-caused. But the way it is presented in the media is considerably exaggerated. We’ve heard that the end of the world will come by the end of the century or even much sooner. We were told that the very rapid increase in temperature that we have seen from the mid-seventies to the late nineties was very dramatic. Then, when the temperature increase stagnated over the last fifteen years, people began to say and think that "it isn't true." A lot of changes happen naturally. Perhaps the most significant of these is the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), which essentially causes temperature to rise and then fall. If the rising temperature coincides with the oscillation, you may notice that sometimes the temperature rises faster and sometimes stabilizes - that’s exactly what we saw in the last century. If you look at the entire process, you will notice a temperature increase that is probably caused by global warming. We are talking about rising sea levels, heat waves, weather fluctuations - we can handle these phenomena quite well, but it costs a lot of money. That’s why it’s a problem and why we would like to avoid it. However, it definitely does not mean the end of humanity. Economic models show that the overall costs of global warming are on the order of 1.5% of GDP. It’s not 0%, but it’s also not 100% and it’s not the end of the world. So let’s make sure we are not spending much more than 1.5% to solve a problem that is on the order of 1.5%. So you’re saying the situation is serious, we should take it into account, but we should be realistic. We need to look at what lies ahead. It’s a topic for the future and it’s also a problem - and as I’ve indicated - a 1.5% problem, not the end of the world. The panic that often accompanies discussions of these issues does not help solutions. It’s about solving a problem over the span of a hundred years, not within the next year. And scaring everyone around is not the right way to achieve smart decisions. When we panic, we make bad decisions like "we must install solar panels right now." But people generally tend to procrastinate until it’s too late. Isn't this a good argument for the market and campaigns regarding these issues? People do not act unless they are pressured - so we need to put pressure on them and sharpen the message a bit. I understand this argument, but we have approached it this way over the past twenty years, and the result is clear: people were initially very scared, then wasted a lot of money, and now they are disillusioned. We have practically achieved nothing other than making people disgusted. Many of them are currently skeptical about global warming because it has been overly presented. If you want people to make the right decisions over the span of decades, scaring them is not a successful tactic. Energy-efficient buildings and costsWhat do you think about energy-efficient buildings and complex certifications?I should preface that I am not an expert in this area. In my opinion, we need to limit emissions from buildings because they significantly contribute to the overall production of global emissions. As for criteria, I think there are many different ideas behind them, some of which are really good, some are not so smart and some might belong to the category of “good feeling” measures. I would like to discuss which criteria are really important and which are just for show. I would be interested in how beneficial the implementation of each is for society, and also how the comparison of the cost of a given measure and its actual benefits comes out. My experience from other fields is that the benefit-cost ratio is from one to one hundred. For every crown invested, you can save up to a hundred crowns on damages or gain a benefit of a hundred crowns. In another area, however, you might gain only a benefit of two crowns for every crown spent - which is still nice, but maybe you should focus on measures with a hundred-crown benefit. However, measuring direct benefits or results is very difficult. You mentioned social aspects; the other two main areas are economic and environmental. How would you currently, in 2013, define sustainability? The simple answer is that we must ensure that future generations are at least as well off as we are. That’s the basic definition. Today we are further along - we want to ensure that life on this planet is good now and remains at least as good in the future. It is largely about ensuring that future generations will have opportunities, options, and knowledge to solve many problems. Probably one of the best ways to do this is to give them better knowledge of how to secure food, how to avoid diseases, and to have more natural resources. It is very important to realize that with these three fundamental pillars we can never go wrong. In reality, however, this is not how it happens - we take care of the economy and then we do something small for the social and environmental issues. How do you behave when a given issue is very beneficial economically - should you strive to shift into social and environmental areas? The honest answer is that you will make a trade-off among these three categories. I understood it as if there is a certain hierarchy - the environmental line should be the most important. But it is true that because of the economic situation, the emphasis is currently more on the economy. As I said, we actually need to trade off among these three goals. And I would have a slight reservation about positioning the environment over the economy because I think they are equally important to us. Of course, we cannot live without the environment, but that is not a threat we face at present. The question is whether we can live in air that is somewhat more polluted. Can we live with a little less forest area? The answer is: Yes, of course we can. But maybe we don't want to - we consciously choose how clean we want the air to be, how many forests we want, and how wealthy we want to be. We decide whether to preserve a forest on the edge of the city or whether to rather build another sixteen apartment buildings there. We are making these choices entirely consciously - I wish everyone would realize this. Because if we were to have an open discussion, it would be much easier for everyone to make a suitable choice democratically. It is important to realize that sometimes we prioritize the economy because we are concerned about money, but sometimes we choose the environment because we want to do good things. How can this principle be applied in construction? We should know the cost of all the things we plan to do. When we go back to buildings, you can financially quantify the benefit of a green roof - how much benefit it brings, what its impact is on cooling offices, how it is watered, how happy employees are, etc. Then these benefits are compared with the incurred costs. Compare how many crowns you get from each invested crown. Recently, there has been increasing discussion about the collection and use of rainwater. What do you think about that? I haven’t done any studies in this regard, but in a well-functioning society with a well-established water management system, I think it’s nonsense to deal with collecting rainwater. Let’s use the municipal water supply. We have a functioning infrastructure built, so there is no need to deal with extra water collection. It would be different in the Sahara. Certainly. I am speaking without knowing exact figures - I come from Denmark, where we have a lot of water. We must of course not waste water, but we have a good water recycling and purification system and we have really clean water available. The beauty of cost-benefit analysis is that you can continuously track what you are spending money on and where it might bring more benefits. What do you think about the LCA method (Life Cycle Assessment)? What method would you recommend for assessing the environmental impacts of products? What I find problematic about the LCA method is the huge list of different outputs and impacts - it deals with the impact of CO2, heavy metals, and many other effects. And there is no defined way of measuring them, which I think is important. If you have to choose between two building materials, you need to rank them in a way so we know how well they perform from an economic point of view. The LCA method is great for getting numbers, but at some point you will have to say how much a ton of CO2 is worth expressed as a common denominator. Economists propose that the common denominator should be money because we already know how to deal with them. Let’s assume that CO2 emissions from a certain building are valued at $60,000, heavy metal emissions at $20, etc. Then you can compare it with other building materials as well. The entire consideration is then easily understandable, which significantly simplifies all discussions. Renewable energy sourcesWhat do you think about all the fuss surrounding renewable energy sources?I clearly see a problem in regulation and in trying to tackle too many issues at once. We have witnessed that companies from energy-intensive sectors in Europe are considering leaving, for example, moving to America, where natural gas is much cheaper. It’s important to keep in mind that when doing something expensive, it has certain consequences. It costs the state money and jobs. That does not mean we should not tackle it - we can decide that reducing carbon emissions is really important to us. But I think it’s very easy to conclude that a style of reduction that is "too much, too quickly, and at very high costs" leads to opposing tendencies. That is why I often say we need to focus much more on research and development, for example, of solar panels and other technologies. If solar panels were available that were cheaper than fossil fuels, everyone would buy them. They would be purchased by Chinese and Indians alike, and everyone would produce much less carbon dioxide emissions. If you are able to offer technology that can compete with fossil fuels or even outperform them, you’ve succeeded! If you can’t, you will forever have to rely on subsidies, which is simply not a good solution. In the Czech Republic, there are two main directions in the discussion about energy: the dominant nuclear one and the smaller one for renewable energy. Neighboring Germany, for instance, is completely moving away from nuclear power and heading towards renewable energy sources. Which direction would you lean towards? A large portion of people will not be willing to draw most of their energy from nuclear in the future. Many people are too afraid of nuclear energy; moreover, nuclear power is currently too expensive, especially considering the costs of disposal when decommissioning nuclear power plants. Therefore, I think we will never see substantial growth in this sector, at least not with the current generation of nuclear power plants. The future, that is the fourth generation, promises to be much cheaper, safer, and easier to install, etc. We have, of course, heard the same about the second and third generations. So let’s wait and see how it evolves. If we focus on nuclear research and development, perhaps solutions will come from this area. If we focus on research and development of renewable energy sources to make them sufficiently cheap, perhaps we will find solutions in this sphere. My opinion is simply that we must get below the price of fossil fuels. I will be satisfied with anything that works; currently, both options are too expensive. What do you think is currently the most interesting innovation in sustainable development? I would mention one example from China. There is a lot of talk about pollution there, which is a completely true statement. People often mention wind turbines and solar panels in this context, but that is completely irrelevant - China gets a negligible amount of energy from wind and solar sources, less than 1%. But there is another story - most people in China are currently acquiring passive solar water heaters, which are placed on the roofs of houses. They are cheap! They are low-tech products. If it’s cloudy for a few days, people must do without hot water, but they are poor, it doesn’t bother them, and they install them - without subsidies, without incentives, simply because they are cheap and work. With this simple step, they reduce China’s carbon dioxide emissions about five times more than all their wind turbines combined. Sustainability means finding cost-effective solutions. Sometimes you are categorized as a right-wing environmentalist. What should we understand by that? I don’t understand that. I think that in a sense, the so-called left-wing environmentalists have focused on global warming, which they view as a major challenge and want to solve. The right, on the other hand, considers warming to be a misstep, something that cannot be trusted - this tendency is clearly visible in the USA. Both of these claims are, in a way, nonsensical. Of course, you cannot firmly say from a purely political standpoint that you do not believe in global warming. It’s similar when you’re from the left and genuinely want to help poor people in the world. You must ask yourself: Is installing solar panels the best way to help future generations and current generations, the poor generations? I constantly encounter people who, for example, talk about helping people with malaria by reducing carbon dioxide emissions. That’s probably the worst and least effective way to help people with malaria. Those people are dying of malaria right now - the whole problem relates to mosquitoes and medicines, a sensitive and smart strategy of help that brings far more benefit at low costs. So sometimes I anger both wings. The right wing because I say that global warming is real, and the left wing because I say that some of their solutions do not work. So I actually stand somewhere in the middle - I try to take the middle path and seek smart, effective solutions. We must make do with the available resources and try to get as much out of them as possible. Author: Mgr. Jaroslav Pašmik, Czech Council for Green Buildings E-mail: jaroslav.pasmik@czgbc.org Translation: Ing. Petra Šťávová, Ph.D. Photo: Emil Jupin

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment

|