<DIV>DRAMATIC INTERSPACE ZDENĚK FRÁNEK</DIV>

Jaromír Sedlák

Motto:

I have nothing against oblique angles or curves, as long as they are done well... Baroque architects knew how to handle these things – but they were at the last stage of a long development.

Mies van der Rohe

Full of merit, yet poetically

A person lives on this earth

Friedrich Hölderlin

Architect Zdeněk Fránek is currently one of the most interesting and stimulating personalities in the architectural scene, not only in Brno but in the Czech Republic as a whole; interest in his work now transcends borders.

A serious question of organic, or if you will, plastic, sculptural or psychologically oriented architecture is primarily its theoretical grasp in the context of professional discourse and its explanation to the broader public.

Fránek does not follow a predetermined scheme; he does not have a closed theoretical, expressive, or material register, intentionally avoids delineating a sharp boundary of the field, does not attempt to firmly and uncompromisingly establish what architecture is, how it should serve, and what it should represent, and what lies outside architecture. His creative thinking follows a path of experimentation, seeking new ways and possibilities, a path of deeper reflections on the nature and meaning of building formation. It is marked by the depth and intensity of an inner compelling inspiration, the strength of a primal vision, and the process of its materialization as a means for an autonomous interpretation of the world, which is filled with the language of building material that cannot be replaced with words or images, but must be experienced directly, and that in the context of the place and its genius loci.

The paradox is that Zdeněk Fránek's work is only beginning to be appreciated at a time when sculptural, plastic, and organic tendencies are increasingly asserting themselves in global architecture, even at a time when these creative processes take on a certain urgency. It seems that a process has been playing out on the global stage for some time now, with which Czech architectural criticism has yet to fully reconcile theoretically.

Western society has long ceased to be traditionally organized hierarchically – vertically, but horizontally as a network. Hierarchical organization and collectivist tendencies remain, in their most robust formal expression, the legacy of leftist ideologies and totalitarian systems. In the same way, a purely technical and materialistic grasp of reality has gradually proven to be misleading and binding to human nature. Modern Western society is individualistic and liberal. From this, it seems, springs the penetrating absence of general order in architecture.

The construction of a family house is a symbol of social individuation, economic status, and an expression of lifestyle. It reflects the mindset of its owner, their anchoring in reality, and their mode of communication with their surroundings. Lifestyle is much more a question of philosophical perception of the world than mere technical standard. A banal standardized family house can be equipped just as well as excellent architecture today, yet it contributes nothing to society and landscape. The choice of architect is decidedly a matter of personal responsibility of the builder.

Fránek's clients are often burdened by an unreasonably long construction time and the demands for atypical and above-standard deliveries - sloped outer walls, curved glass, and so on. It can be said with exaggeration that Fránek's houses do not just get built; they grow like an organism. The architect himself says about this: "My house grows into the parcel and its surroundings like a mushroom into the trunk of a tree."

Zdeněk Fránek does not like the literary expression of a story in connection with his works – a house for him is not a story, but an independent work of art. Nevertheless, it must be said that each of his houses undoubtedly has its own story – from the meeting with the client, from the first sketch to countless variations and modifications of the project until the solution of unusual details. Some of the stories culminate in complex realizations and ultimately find fulfillment through the experiences of everyday life, while others end with models and drawings.

Fránek's houses can never be standard. At a time when Le Corbusier wrote in his famous book Towards a New Architecture about how houses of the future should resemble airplanes, ocean liners, and cars, it might have seemed that all this would one day be possible. During this fortunate period between the catastrophes of both world wars, the development of technology met abstract aesthetics and gave rise to constructivism and functionalism. Ultimately, however, technology is inexorably following its own path, and today it is almost absurd to demand that residential buildings look and function like jet aircraft or the latest car models, to be constructed and mass-produced.

A chasm has been excavated between high technology and the art of construction, which cannot be bridged with available means today. Moreover - clients in overwhelming majority ask for something entirely different. People love their cars, can hardly do without electronics, and travel en masse by plane. However, from their house, they expect something different. They want a shell that protects their privacy and the everyday poetry of ordinary life, they long for contact with the terrain of the garden and the plants, and they yearn for a beautiful view. The world of science and technology should serve life, not completely control it.

It is individual family living that raises serious questions related to the creation of space. What human needs should or can a building fulfill, or what further and new qualities can a house bring into the lives of its residents? While physical and material needs can be quite precisely defined and fulfilled by available technical means, the psychological needs and desires of the house builder are the subject of complex and exhaustive discussion among the client, members of their family, and the creator of the final form – the architect.

Clients of Zdeněk Fránek are certainly not people who expect merely the usual standard from a family house. They embark on a complicated path of cooperation, where the assignment of a family house becomes a challenge to fulfill a vision that is capable of encompassing not just the spirit of the age and the unmistakable handwriting of the author, but also to examine deeper questions regarding the meaning of existence of a house and its connection to a unique place. The reward for this challenging process is the opportunity to experience daily the uniqueness of building material, to inhabit a house filled with intense experiences of space and light, which imprints itself into the memory of a sensitive person and leaves a lasting mark on their soul. A client's commentary aptly summarizes this: "I knew that whatever house I create should deserve its right to exist. Due to its value. When you plant a tree, it shouldn’t be just for this moment... if I could design myself, I would probably look somewhere between shapes such as a cube or an ellipse: somewhere among the perfections. Fránek found a way to enrich my musing about something absolute or minimal with artistic thoughts."

The family house in Hodonín vaguely resembles two interconnected ceramic vessels from the Great Moravian period. Overall, it has a distinctly surreal impression, akin to a mysterious body from a painting by René Magritte or Max Ernst. Fránek verified here two immensely important things – building curved ceramic shells by “freehand,” meaning without the aid of continuous formwork, and secondly the impressiveness of large smooth and essentially unarticulated volumes of the building and their almost magical attractiveness and strength. Rostislav Švácha pointed out that the house almost feels like a sacred building and raised the question of whether such an expression is appropriate for the function of housing – he was not mistaken. Fránek indeed tends towards forming a quasi-sacred character in the central space of family houses. He does not actually perceive a sharp division between the sacred and the profane, but rather constantly examines and seeks the balance of expression and function. The idea of the Hodonín house was further developed in an unrealized project for a church in the Lesná housing estate, based on a similar principle of a brick vault with two shells, between which a staircase was to rise. Fránek is fascinated by the double shell of the building, the artistic possibilities offered by this ambiguous interface between “outside” and “inside.”

After ten years of tireless creative work, honing forms of architectural language, and searching for the optimal degree of expression, Zdeněk Fránek indeed reached the fulfillment of his thoughts in the realization of two sacred buildings – chapels of the Brotherhood Church. In the Hodonín house, we feel a tension stemming from the contrast of several diverse volumes and their scales, as well as from the imprint of living spaces into the bowels of the sculpturally felt mass. It is exactly this discord and the effort to resolve it that drove Zdeněk Fránek's creative activity for so long until he found means to bring form and content into mutual harmony and to establish a balance between the interior and the skin of the building.

To solve this equation, Fránek was led by two seemingly completely opposite inspirations: it was the exploration of artistic means and possibilities of contemporary minimalism and the influence of Tadao Ando’s work on the one hand, and a deep life fascination with the buildings of Jan Blažej Santini on the other.

Santini's work is characterized by a pure monumental internal space, devoid of excessive decoration, as if flooded with bright cold light from various sides and angles. For Baroque thinking, the idea of universal harmony had a key significance, stemming both from rational knowledge of the world and from its religious interpretation. Such unity, which the Baroque building tries to present to the viewer comprehensively, is, however, no longer possible today. This concept was gradually dismantled and replaced by a postmodern plurality of thought, allowing for various hypotheses for interpreting the world. Zdeněk Fránek, however, is not inspired by historical Baroque morphology but instead pursues the deeper, timeless qualities of Santini's unique work, which have transcended their time. He is influenced and affected precisely by the extraordinary strength and urgency that a building is capable of conveying: "Yes, Santini's buildings feel like revelations from another world, like an abnormally enlarged natural object - a fruit or crystal that unexpectedly sprouts from the ground and dominates the landscape. That is how they were conceived, for unique and exceptional experience." says Zdeněk Fránek.

The scientific development of geometry at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries opened new possibilities for artistically grasping the properties of curves, elliptical shapes, warped surfaces, and rotational bodies. The use of the formal and spatial qualities of these forms and their artistic application in the expression of buildings, as well as the exploration of the spiritual properties of light, became leading themes of Baroque art.

Generally, it is believed that the intense effort of Baroque towards maximum expressiveness, up to ecstasy achieved by all then-available means, is something that has no place in modern architecture. The intrinsic temporal interest in spatial and artistic illusions, pushing the boundaries of human perception beyond reality, may seem somewhat amusing today – how could it be otherwise when we are currently the targets of mass-produced illusions in film, video art, or advertising? The world of illusions today is much more powerful and manipulative, armed with limitless technical means and tremendous mass-impacting strength.

However, this does not change the fact that some contents and experiences can be conveyed only by a true building, which extracts a small portion of space from the landscape to create its own micro-world.

The house is shaped by the dialogue of two shells, expressed by two completely different materials – exposed concrete and wood. In reality, the building resembles a structure that has grown, turned inward – separate rooms and spaces are enclosed within themselves, sharing a relationship similar to medieval houses squeezed together in a small space. An important idea of the project is working with the space between the two shells – it is precisely this interspace that particularly interests the author. There is no sharp boundary for Fránek between the inside and outside of the building; it is a place of communication, movement, semi-shadow, and a certain mystery. This ancient architectural motif runs through Zdeněk Fránek's thinking like a red thread in various forms. We find it in all significant epochs of building art from ancient times to the present. Outwardly, however, the facade can be entirely smooth and closed like an archaic barn, only articulated by a wooden bay window that responds to a similar motif of the neighboring Renaissance castle – the present town hall.

The life and work of Zdeněk Fránek is marked by the landscape of the Moravian Karst. Certainly, it is not just because he was born in this beautiful mythical land – in Boskovice – fifty years ago and still lives in Boskovice today. The family house built in a landscape broadly open to views stands out with the vividness of its form. The slanted roof rests against a massive northern wall, whose sporadic abstract articulation by window slits has the solidity of a rock wall. However, on the southern side, wood predominates, manifested in this case in an essentially rural inspiration – a horizontal beam in the shape of a ladder that supports the roof structure. The composition recalls the generosity of the masses of rural barns and buildings. The author says: "Simply put: I took a twenty-six-meter ladder one meter wide with steps one meter high made of glued beams. I set (suspended) it on brackets made from pieces of limestone embedded in free-standing walls. On this hanging ladder, I placed the roof of the entire house and glazed some of the ladder's fields as windows. The ladder will thus remain a once abundant part of the structure of rural reality forever."

This original work has a unique charm – it bears the barely perceptible seal of its birth, searching, and original thinking, with a light patina of fine imperfection accompanying everything that is discovered and realized with difficulty. Yes, Zdeněk Fránek also adopts various influences and inspirations that affect his work. However, the formation of his personality never allows him to copy or work conventionally.

The volume of the house rests on a sloping plot and an older basement. The building evokes a striking impression of a seaside villa, primarily due to extensive terraces and smooth white plastered walls, which more closely resemble the works of Alvaro Siza than the language of Brno functionalism. The sharp angle between the two wings of the house derives from the shape of the plot and the orientation of living spaces to ensure maximum views of the valley and the wooded hill opposite. Zdeněk Fránek here fully exploits the geometry of oblique crystalline surfaces and skew angles while entirely abandoning the use of arches and curves. At the center of the layout is the dominant element of a straight staircase, majestically positioned between two rows of dense solid reinforced concrete columns, whose natural surface, subtly articulated with spirals of formwork, sharply contrasts with the smooth light troweled floor. Thus, the house visitor first perceives the archaic expression of the colonnade, which evokes an almost ancient or Romanesque impression, while the visual entrance axis of the interior culminates at the fireplace in the main living area. Only then – slowly – do surprising and breathtaking views open up, offered by strip windows in subtle stainless steel frames. The layout of the house appears almost unreadable, and the composition of individual rooms lacks the seemingly usual geometric order – yet it evokes a natural and relaxed impression. The house, indeed, again acts as a grown structure, firmly rooted in the terrain, while the brackets of the terraces and the slanted concrete pillar elegantly articulate the facade, evoking the impression of growth and airily and boldly extending the mass of the building into the garden. The top floor, which contains the bedrooms, forms a very gentle angle, and the dramatic form is crowned here by the purity of the line that closes the building off and delineates it against the sky. The house combines several almost contradictory themes, offering numerous everyday spatial experiences that the residents can appreciate very well. We find contrasts of forms, materials, spatial concepts here, yet the resulting form is convincing. It is architecture based primarily on the crystalline play of volumes, angles, and smooth surfaces that break and reflect the light. The effect of the structure is enhanced by a minimalist detail that draws attention to what is truly essential.

It is remarkable that Zdeněk Fránek here filled the vision of a building as a white rhomboidal crystal just before similar concepts began to be significantly applied in the pages of foreign professional magazines. I see this as the author's ability to sense and anticipate the emerging spirit of the age, to find a complex yet purified form on his own path and with unique means.

Hundreds of thousands of family houses built from the nineties up to today are nothing more than an explosion of suppressed and distorted desire for freedom, privacy, and self-expression of spiritually leveled beings. Mass construction of individual housing has degenerated into its true opposite, a settlement mash without style and opinion, collective tastelessness and a parody of the garden city with elements borrowed from the vocabulary of cottage colonies. The average Czech house has not yet decided what it actually wants to be – to put it in the words of L. I. Kahn. Does it want to be a rural cottage (for it is where the roots of most of us lie), or an aristocratic residence (for we occasionally secretly yearn for that when visiting castles and manors), or perhaps an exclusive villa, the comfort of which we need for life? The architect thus stands like Don Quixote against the current, a sad knight equipped only with his courage and ideals.

However, sometimes a small miracle occurs, and a person who commissioned a worthless American bungalow on a flat regular plot suddenly calls architect Fránek, and within three days, a completed but banal project is thrown into the trash can, and he starts over once again – to create a house that deserves its right to existence. This is exactly how the concrete house in Prague came to be.

It might seem that here reason completely triumphs; the architect subordinates the square footprint to the rectangular plot and the nature of the client – precisely delineating the regular outlines of the rooms and the proportions of the wings. Yet, here too, light play and a sense of mystery have their place. It almost seems that the house slightly hovers above the English lawn. A deep notch in the shadow of the gray roof allows light to penetrate into the heart of the layout. Everywhere there is order and precision, sensitive geometry that has its soft transcendence beyond the boundaries of the known world of forms. Here, we feel a hint of transcendence that peaks later – in the construction of the Czechoslovak Brotherhood Church in Litomyšl.

The common denominator of minimalism and Baroque in Fránek's interpretation is similar, albeit achieved by completely different means: it is the fragile predominance of spirit over matter. The spiritual flavor of the concrete house is impossible to overlook.

It might seem that Fránek's houses, which occasionally lie on the edge of the technical capabilities of contemporary Czech construction – moreover, placing high intellectual demands on their inhabitants – are something completely exceptional, a luxury for a few chosen ones. However, Zdeněk Fránek can create an extraordinarily strong house even on a minimal budget – the proof is the family house in Ráječko, built partially with the owner's help at the price of an apartment.

The hard concrete shell of the prism protects a soft insulating core made of birch plywood, which lends its color and texture to the interior. This house is entirely archetypal due to the enforced formal simplicity. "The only curve is the bend on the roof, creating a gutter through which water flows out." says the author. The house is much more than just a concrete box and overcomes the ingrained conception of a cheap house by the strength of its concept in every respect, primarily due to creative collaboration with the client.

The exploration of the interaction between the stark concrete frame of the building and the transparent membrane culminates in an unrealized project for a house in Prague. The glass wall is no longer just a neutral surface that brings light and landscape images; it surrenders to the energy of life flowing through the house. The dramatic interspace of Zdeněk Fránek here culminates in a form on the boundary between a sculpture, a musical composition, and a conceptual work. The spiral staircase dynamically bulges the glass shell of the house outward and creates new relationships between vertical and horizontal movement within the house and the perception of the garden.

In the Baroque period, philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz gave birth not only to differential and integral calculus, which still serves today to mathematically grasp curves, but also to the concept of monad – a particle – the primal basis of being and point-like substance. A body is therefore nothing more than a point center and simultaneously a force center. The monad, however, is also a soul. It is hard to shake the impression that a similar understanding of being subconsciously comes alive in this Fránek project. After all – the architect himself considers a Baroque building as an extended musical instrument.

A villa that grows into the terrain, resembling a massive protective shell. The massive mass of the curved wall, like a fortress safeguarding everyday life within – is only breached by occasional horizontal embrasures of small windows. In contrast, the southern facade opens to the garden like a sensitive embrace, allowing the garden to flow into the interior. Nothing more. The sloping roof descends against the direction of the terrain. The sharp-cut corner is merely the outlet of the mutual contact of these two shells, not just an abstract game of shapes. The loggia captures the vibrations of the air at the boundary between the house and the outside world like a taut string of a harp. The weight of the forms is softened by delicate half-shade, and the plastic ribbed plaster preserves the imprint of the human hand. The house does not attempt to pretend to be perfect; it acknowledges how it was built. The structure captures light like fabric or skin while resonating with the form and guiding the eye in the direction of the curvature.

The Baroque is often criticized for its lack of integrity between outer and inner space. However, I am convinced that this is a fallacy. Baroque facades convincingly reflect the character of the building – if there is any tension between form and content, it is only because certain sensations and messages are meant to remain concealed from the viewer until they step inside to understand.

Between the interior and exterior of a Baroque building, there is often a third zone – let’s also call it the interspace – that mediates contact between the two spheres so that the transition is smooth and stepwise. These are various antechambers, empore, galleries, and staircases that filter daylight penetrating inside, enveloping the central inner space and frequently integrating the supporting system of the building.

All of this can be found in the space of the Brno villa, albeit in subtle hints. The spiral external and internal ramp defining the conical perimeter of the house is not merely a vertical communication, connecting different height levels of the outer and inner space, but becomes a means through which the shell of the building can be experienced over time as a changing dialogue of mass and light that delineates the everyday rhythm of life in the house. At the same time, Zdeněk Fránek wrote with this house a new chapter of contemporary villa architecture in which he responded to some questions raised, for example, by Bohuslav Fuchs in two buildings from the end of the 1930s – the Petrák and Tesař villas in Masaryk quarter. The connection with the organic tendency of interwar architecture here, however, was not the author's intention – it arose naturally from the essence of the task and its method of mastery.

In this house, it does not hold that the space has the same quality in all points; it is a dynamic center capable of binding and concentrating the energy of the place and the plot; the Cartesian coordinate system applies only partially and conditionally here. The dynamics of the movement of light through the house moves the villa towards a place between a musical composition and a sculpture, yet it remains primarily an elegant building.

Zdeněk Fránek is literally obsessed with the power of his thoughts and inspirations that he seeks to materialize. On the path toward realizing his vision of architecture, he has traveled a long road. He is a visionary and an experimenter par excellence. It is precisely the independent creative path, the deep search for the essence of his work and its meaning, the passing the mainstream, and the urgency of spontaneous imagination, occasional wanderings and failures, all contribute a seal of originality to Zdeněk Fránek's work, but above all an inner authenticity. It is possible that many elements of Fránek's language will ultimately penetrate into the broader vocabulary of forms and be generally accepted. The appreciation of Zdeněk Fránek's work takes place slowly and gradually, while his buildings penetrate the pages of foreign books and magazines. Suddenly, we begin to awaken and feel that without this author, the image of our contemporary architecture would not be complete – it would be poorer and more monotonous.

In these days, an exhibition of the works of Zdeněk Fránek’s studio is taking place at the Brno House of Art under the title The Intestines of Architecture. The very grasp of the exhibition space and the way of presentation allow us to glimpse beneath the surface – into the world of nascence and development of ideas and concepts from which the buildings draw their strength. We would vainly search here for photographs, glittering visualizations, and exhaustive accompanying texts. Fránek does not offer us his theory, does not explain or instruct, does not seek to justify himself – he tries to open the mind and imagination of the viewer to the experience. The exhibited models of buildings have great urgency, themselves functioning as coherent artifacts regardless of scale, captivating the viewer with their materials and guiding our imagination into their uniquely diverse worlds. The exhibition leaves an indelible imprint of poetry somewhere deep in the subconscious. The white models of houses float on the black water surface like autumn leaves, and we cannot help but think of the words of the painter Jánuš Kubíček: Life gradually emerged from the sea, and we do not feel like plagiarists of fish, amphibians, or reptiles. Art does the same as nature: it carries the marks of its predecessors. There is no reason to be ashamed; quite the contrary. Let us realize that perfection was before us – and let it be a postulate for us. Here, the fun ends; the measure is the eternal flowing time…

It can be said that Fránek has ascended heights and descended to depths, bringing back valuable experiences and precious insights. It cannot be excluded that soon imitators and epigones will appear, who will extract valuable sources of inspiration from Fránek’s creations and adopt as ready those principles that Zdeněk Fránek arrived at gradually, painfully, and slowly. Such is the fate of visionaries.

I have nothing against oblique angles or curves, as long as they are done well... Baroque architects knew how to handle these things – but they were at the last stage of a long development.

Mies van der Rohe

Full of merit, yet poetically

A person lives on this earth

Friedrich Hölderlin

|

| Family House in Plzeň (photo: Studio Petrohrad) |

A serious question of organic, or if you will, plastic, sculptural or psychologically oriented architecture is primarily its theoretical grasp in the context of professional discourse and its explanation to the broader public.

Fránek does not follow a predetermined scheme; he does not have a closed theoretical, expressive, or material register, intentionally avoids delineating a sharp boundary of the field, does not attempt to firmly and uncompromisingly establish what architecture is, how it should serve, and what it should represent, and what lies outside architecture. His creative thinking follows a path of experimentation, seeking new ways and possibilities, a path of deeper reflections on the nature and meaning of building formation. It is marked by the depth and intensity of an inner compelling inspiration, the strength of a primal vision, and the process of its materialization as a means for an autonomous interpretation of the world, which is filled with the language of building material that cannot be replaced with words or images, but must be experienced directly, and that in the context of the place and its genius loci.

|

Western society has long ceased to be traditionally organized hierarchically – vertically, but horizontally as a network. Hierarchical organization and collectivist tendencies remain, in their most robust formal expression, the legacy of leftist ideologies and totalitarian systems. In the same way, a purely technical and materialistic grasp of reality has gradually proven to be misleading and binding to human nature. Modern Western society is individualistic and liberal. From this, it seems, springs the penetrating absence of general order in architecture.

The construction of a family house is a symbol of social individuation, economic status, and an expression of lifestyle. It reflects the mindset of its owner, their anchoring in reality, and their mode of communication with their surroundings. Lifestyle is much more a question of philosophical perception of the world than mere technical standard. A banal standardized family house can be equipped just as well as excellent architecture today, yet it contributes nothing to society and landscape. The choice of architect is decidedly a matter of personal responsibility of the builder.

Zdeněk Fránek does not like the literary expression of a story in connection with his works – a house for him is not a story, but an independent work of art. Nevertheless, it must be said that each of his houses undoubtedly has its own story – from the meeting with the client, from the first sketch to countless variations and modifications of the project until the solution of unusual details. Some of the stories culminate in complex realizations and ultimately find fulfillment through the experiences of everyday life, while others end with models and drawings.

Fránek's houses can never be standard. At a time when Le Corbusier wrote in his famous book Towards a New Architecture about how houses of the future should resemble airplanes, ocean liners, and cars, it might have seemed that all this would one day be possible. During this fortunate period between the catastrophes of both world wars, the development of technology met abstract aesthetics and gave rise to constructivism and functionalism. Ultimately, however, technology is inexorably following its own path, and today it is almost absurd to demand that residential buildings look and function like jet aircraft or the latest car models, to be constructed and mass-produced.

|

It is individual family living that raises serious questions related to the creation of space. What human needs should or can a building fulfill, or what further and new qualities can a house bring into the lives of its residents? While physical and material needs can be quite precisely defined and fulfilled by available technical means, the psychological needs and desires of the house builder are the subject of complex and exhaustive discussion among the client, members of their family, and the creator of the final form – the architect.

Clients of Zdeněk Fránek are certainly not people who expect merely the usual standard from a family house. They embark on a complicated path of cooperation, where the assignment of a family house becomes a challenge to fulfill a vision that is capable of encompassing not just the spirit of the age and the unmistakable handwriting of the author, but also to examine deeper questions regarding the meaning of existence of a house and its connection to a unique place. The reward for this challenging process is the opportunity to experience daily the uniqueness of building material, to inhabit a house filled with intense experiences of space and light, which imprints itself into the memory of a sensitive person and leaves a lasting mark on their soul. A client's commentary aptly summarizes this: "I knew that whatever house I create should deserve its right to exist. Due to its value. When you plant a tree, it shouldn’t be just for this moment... if I could design myself, I would probably look somewhere between shapes such as a cube or an ellipse: somewhere among the perfections. Fránek found a way to enrich my musing about something absolute or minimal with artistic thoughts."

Family House Rybáře, Hodonín, 1998

|

After ten years of tireless creative work, honing forms of architectural language, and searching for the optimal degree of expression, Zdeněk Fránek indeed reached the fulfillment of his thoughts in the realization of two sacred buildings – chapels of the Brotherhood Church. In the Hodonín house, we feel a tension stemming from the contrast of several diverse volumes and their scales, as well as from the imprint of living spaces into the bowels of the sculpturally felt mass. It is exactly this discord and the effort to resolve it that drove Zdeněk Fránek's creative activity for so long until he found means to bring form and content into mutual harmony and to establish a balance between the interior and the skin of the building.

|

Santini's work is characterized by a pure monumental internal space, devoid of excessive decoration, as if flooded with bright cold light from various sides and angles. For Baroque thinking, the idea of universal harmony had a key significance, stemming both from rational knowledge of the world and from its religious interpretation. Such unity, which the Baroque building tries to present to the viewer comprehensively, is, however, no longer possible today. This concept was gradually dismantled and replaced by a postmodern plurality of thought, allowing for various hypotheses for interpreting the world. Zdeněk Fránek, however, is not inspired by historical Baroque morphology but instead pursues the deeper, timeless qualities of Santini's unique work, which have transcended their time. He is influenced and affected precisely by the extraordinary strength and urgency that a building is capable of conveying: "Yes, Santini's buildings feel like revelations from another world, like an abnormally enlarged natural object - a fruit or crystal that unexpectedly sprouts from the ground and dominates the landscape. That is how they were conceived, for unique and exceptional experience." says Zdeněk Fránek.

The scientific development of geometry at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries opened new possibilities for artistically grasping the properties of curves, elliptical shapes, warped surfaces, and rotational bodies. The use of the formal and spatial qualities of these forms and their artistic application in the expression of buildings, as well as the exploration of the spiritual properties of light, became leading themes of Baroque art.

Generally, it is believed that the intense effort of Baroque towards maximum expressiveness, up to ecstasy achieved by all then-available means, is something that has no place in modern architecture. The intrinsic temporal interest in spatial and artistic illusions, pushing the boundaries of human perception beyond reality, may seem somewhat amusing today – how could it be otherwise when we are currently the targets of mass-produced illusions in film, video art, or advertising? The world of illusions today is much more powerful and manipulative, armed with limitless technical means and tremendous mass-impacting strength.

However, this does not change the fact that some contents and experiences can be conveyed only by a true building, which extracts a small portion of space from the landscape to create its own micro-world.

Family House in Jaroměřice near Jevíčko

|

| photo: Ester Havlová |

|

Family House with a Ladder in the Moravian Karst, 1997

|

| photo: Radovan Boček |

|

| photo: Radovan Boček |

Family House under Chochola, Brno, 2004

|

| photo: Libor Stavjaník |

The volume of the house rests on a sloping plot and an older basement. The building evokes a striking impression of a seaside villa, primarily due to extensive terraces and smooth white plastered walls, which more closely resemble the works of Alvaro Siza than the language of Brno functionalism. The sharp angle between the two wings of the house derives from the shape of the plot and the orientation of living spaces to ensure maximum views of the valley and the wooded hill opposite. Zdeněk Fránek here fully exploits the geometry of oblique crystalline surfaces and skew angles while entirely abandoning the use of arches and curves. At the center of the layout is the dominant element of a straight staircase, majestically positioned between two rows of dense solid reinforced concrete columns, whose natural surface, subtly articulated with spirals of formwork, sharply contrasts with the smooth light troweled floor. Thus, the house visitor first perceives the archaic expression of the colonnade, which evokes an almost ancient or Romanesque impression, while the visual entrance axis of the interior culminates at the fireplace in the main living area. Only then – slowly – do surprising and breathtaking views open up, offered by strip windows in subtle stainless steel frames. The layout of the house appears almost unreadable, and the composition of individual rooms lacks the seemingly usual geometric order – yet it evokes a natural and relaxed impression. The house, indeed, again acts as a grown structure, firmly rooted in the terrain, while the brackets of the terraces and the slanted concrete pillar elegantly articulate the facade, evoking the impression of growth and airily and boldly extending the mass of the building into the garden. The top floor, which contains the bedrooms, forms a very gentle angle, and the dramatic form is crowned here by the purity of the line that closes the building off and delineates it against the sky. The house combines several almost contradictory themes, offering numerous everyday spatial experiences that the residents can appreciate very well. We find contrasts of forms, materials, spatial concepts here, yet the resulting form is convincing. It is architecture based primarily on the crystalline play of volumes, angles, and smooth surfaces that break and reflect the light. The effect of the structure is enhanced by a minimalist detail that draws attention to what is truly essential.

It is remarkable that Zdeněk Fránek here filled the vision of a building as a white rhomboidal crystal just before similar concepts began to be significantly applied in the pages of foreign professional magazines. I see this as the author's ability to sense and anticipate the emerging spirit of the age, to find a complex yet purified form on his own path and with unique means.

|

| photo: Libor Stavjaník |

Concrete House, Prague, 2001

|

| photo: Ester Havlová |

However, sometimes a small miracle occurs, and a person who commissioned a worthless American bungalow on a flat regular plot suddenly calls architect Fránek, and within three days, a completed but banal project is thrown into the trash can, and he starts over once again – to create a house that deserves its right to existence. This is exactly how the concrete house in Prague came to be.

It might seem that here reason completely triumphs; the architect subordinates the square footprint to the rectangular plot and the nature of the client – precisely delineating the regular outlines of the rooms and the proportions of the wings. Yet, here too, light play and a sense of mystery have their place. It almost seems that the house slightly hovers above the English lawn. A deep notch in the shadow of the gray roof allows light to penetrate into the heart of the layout. Everywhere there is order and precision, sensitive geometry that has its soft transcendence beyond the boundaries of the known world of forms. Here, we feel a hint of transcendence that peaks later – in the construction of the Czechoslovak Brotherhood Church in Litomyšl.

The common denominator of minimalism and Baroque in Fránek's interpretation is similar, albeit achieved by completely different means: it is the fragile predominance of spirit over matter. The spiritual flavor of the concrete house is impossible to overlook.

|

| photo: Ester Havlová |

Family House in Ráječko, 2007 - 2010

|

The hard concrete shell of the prism protects a soft insulating core made of birch plywood, which lends its color and texture to the interior. This house is entirely archetypal due to the enforced formal simplicity. "The only curve is the bend on the roof, creating a gutter through which water flows out." says the author. The house is much more than just a concrete box and overcomes the ingrained conception of a cheap house by the strength of its concept in every respect, primarily due to creative collaboration with the client.

|

Family House Ondřich in Prague, 2008

To understand the meaning and significance of the Baroque era, we must journey approximately three hundred years against the current of time to the period around 1700, when profound changes in the structure of European thought, culminating in the emergence of modern science, are slowly and gradually preparing. Cartesian geometry is certainly not the only possible and correct approach to the world. There are also other forms of order and systems of perceiving space. Exaggerating, we can say that Zdeněk Fránek is constantly seeking such possibilities. He does not oppose rectangular geometry; he just does not consider it the only possible way. |

The exploration of the interaction between the stark concrete frame of the building and the transparent membrane culminates in an unrealized project for a house in Prague. The glass wall is no longer just a neutral surface that brings light and landscape images; it surrenders to the energy of life flowing through the house. The dramatic interspace of Zdeněk Fránek here culminates in a form on the boundary between a sculpture, a musical composition, and a conceptual work. The spiral staircase dynamically bulges the glass shell of the house outward and creates new relationships between vertical and horizontal movement within the house and the perception of the garden.

In the Baroque period, philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz gave birth not only to differential and integral calculus, which still serves today to mathematically grasp curves, but also to the concept of monad – a particle – the primal basis of being and point-like substance. A body is therefore nothing more than a point center and simultaneously a force center. The monad, however, is also a soul. It is hard to shake the impression that a similar understanding of being subconsciously comes alive in this Fránek project. After all – the architect himself considers a Baroque building as an extended musical instrument.

Project for Family House Konopiště

The unrealized design of an exclusive glass house for Konopiště represents a different approach. It consists of a transparent curved facade that continuously envelops the mass of the building, while the layout of the house is organized around three cylindrical atriums and the overall shape of the house is wrapped in bamboo slats like the straws of a bird's nest, adding lightness to the volume, connecting the mass of the building with the landscape and terrain, and further emphasizing the sense of transparency. The bamboo membrane serves as a soft transition between the technical starkness of glass and the surrounding landscape. The boundary between the inner and outer space is thus mild and fluid, the interspace is airy and fragile. |

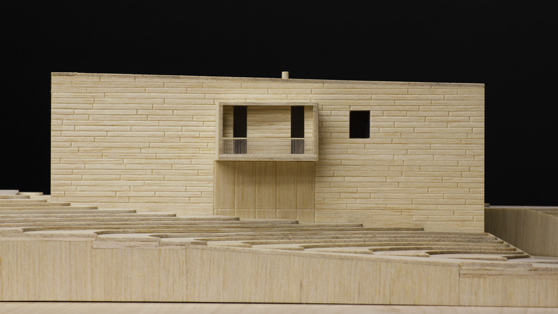

Family House Kriegerbeck in Plzeň

|

| photo: Studio Petrohrad |

|

| photo: Studio Petrohrad |

Family House on the Red Hill, Brno, 2005

|

| photo: Ester Havlová |

Between the interior and exterior of a Baroque building, there is often a third zone – let’s also call it the interspace – that mediates contact between the two spheres so that the transition is smooth and stepwise. These are various antechambers, empore, galleries, and staircases that filter daylight penetrating inside, enveloping the central inner space and frequently integrating the supporting system of the building.

All of this can be found in the space of the Brno villa, albeit in subtle hints. The spiral external and internal ramp defining the conical perimeter of the house is not merely a vertical communication, connecting different height levels of the outer and inner space, but becomes a means through which the shell of the building can be experienced over time as a changing dialogue of mass and light that delineates the everyday rhythm of life in the house. At the same time, Zdeněk Fránek wrote with this house a new chapter of contemporary villa architecture in which he responded to some questions raised, for example, by Bohuslav Fuchs in two buildings from the end of the 1930s – the Petrák and Tesař villas in Masaryk quarter. The connection with the organic tendency of interwar architecture here, however, was not the author's intention – it arose naturally from the essence of the task and its method of mastery.

In this house, it does not hold that the space has the same quality in all points; it is a dynamic center capable of binding and concentrating the energy of the place and the plot; the Cartesian coordinate system applies only partially and conditionally here. The dynamics of the movement of light through the house moves the villa towards a place between a musical composition and a sculpture, yet it remains primarily an elegant building.

|

| photo: Ester Havlová |

Zdeněk Fránek is literally obsessed with the power of his thoughts and inspirations that he seeks to materialize. On the path toward realizing his vision of architecture, he has traveled a long road. He is a visionary and an experimenter par excellence. It is precisely the independent creative path, the deep search for the essence of his work and its meaning, the passing the mainstream, and the urgency of spontaneous imagination, occasional wanderings and failures, all contribute a seal of originality to Zdeněk Fránek's work, but above all an inner authenticity. It is possible that many elements of Fránek's language will ultimately penetrate into the broader vocabulary of forms and be generally accepted. The appreciation of Zdeněk Fránek's work takes place slowly and gradually, while his buildings penetrate the pages of foreign books and magazines. Suddenly, we begin to awaken and feel that without this author, the image of our contemporary architecture would not be complete – it would be poorer and more monotonous.

In these days, an exhibition of the works of Zdeněk Fránek’s studio is taking place at the Brno House of Art under the title The Intestines of Architecture. The very grasp of the exhibition space and the way of presentation allow us to glimpse beneath the surface – into the world of nascence and development of ideas and concepts from which the buildings draw their strength. We would vainly search here for photographs, glittering visualizations, and exhaustive accompanying texts. Fránek does not offer us his theory, does not explain or instruct, does not seek to justify himself – he tries to open the mind and imagination of the viewer to the experience. The exhibited models of buildings have great urgency, themselves functioning as coherent artifacts regardless of scale, captivating the viewer with their materials and guiding our imagination into their uniquely diverse worlds. The exhibition leaves an indelible imprint of poetry somewhere deep in the subconscious. The white models of houses float on the black water surface like autumn leaves, and we cannot help but think of the words of the painter Jánuš Kubíček: Life gradually emerged from the sea, and we do not feel like plagiarists of fish, amphibians, or reptiles. Art does the same as nature: it carries the marks of its predecessors. There is no reason to be ashamed; quite the contrary. Let us realize that perfection was before us – and let it be a postulate for us. Here, the fun ends; the measure is the eternal flowing time…

It can be said that Fránek has ascended heights and descended to depths, bringing back valuable experiences and precious insights. It cannot be excluded that soon imitators and epigones will appear, who will extract valuable sources of inspiration from Fránek’s creations and adopt as ready those principles that Zdeněk Fránek arrived at gradually, painfully, and slowly. Such is the fate of visionaries.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

wow

Tomáš V.

06.01.12 10:11

show all comments