Arnošt Hošek: Mona Lisa

If we list the history of art, we will not find a picture of a woman that we could claim shines with the light of eternity. Even less do the memories of the originals we have seen in reality convince us of this. Painting a female portrait is an ungrateful task. If someone painted a woman out of love, they do not transfer their own feelings to the viewer, whereas photography sometimes evokes similar feelings, perhaps paradoxically, as the realistic camera replaces the sensitivity of the painter. In sculpture, the charm of a woman is closer to us than in a painting. A picture of a woman may be beautiful, provided it is not a portrait. In female portraits, photography perhaps most of all has replaced painting—unless it is a memory that was not captured by the camera. Thus, the past reconciles with the present. In the painting, we marvel at femininity, not at the woman. I will cite the famous portrait of the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci as an example. The painting is more than a portrait, and from that arises all the contradictory opinions. The ordinary person does not like the painting, and because it is not an image of a saint, there arise also conjectures about this woman's chastity. Many people intend to elevate themselves above Leonardo by condemning this painting. In H. W. van Loon's "Art," that opinion is also found, that Leonardo da Vinci could not even paint. — Holiness, of course, only protects Christian images. Figures from mythology are today misused even as commercial brands. Even the popular but nonetheless underappreciated Mona Lisa was not spared from advertising misuse. Once, the Mona Lisa was a fashion. It is often claimed that the current painting is not the original, that it was exchanged for a less successful copy after the theft. But these criticisms have not harmed the painting in any way; it remains perfect despite them. Some primitives see this perfection in the eyes of the Mona Lisa, which move along with the viewer. Admiration alternates with hatred, cleverness with foolishness, etc. In condemning Leonardo, the critic inadvertently condemns himself; even admiration reflects the measure of comprehension. But the sympathy that alternates with complete rejection, the overall human relationship to this painting creates its value among other works of art. Leonardo is a kind of dictator from another world, and everyone should bow at least once in their life to his genius. In his genius lies universal wisdom; he united what no one had succeeded in doing before: art with science. He is a genius of tireless diligence, he is universal, encompassing everything—humor, the calmness of eternity, and the cruelty of death. Michelangelo and Beethoven, alongside him—freed—are bound by human passions. The beauty of their art draws from the deficiencies of human life. Despite that, they are more valued than Leonardo. Perfection intimidates the average viewer, but for others, it allows them to transcend the difficult moments of life.

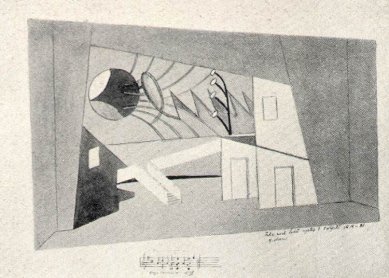

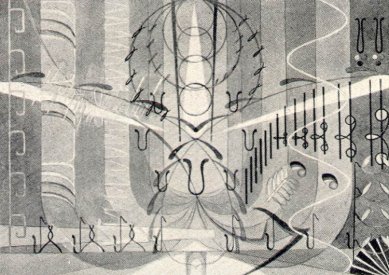

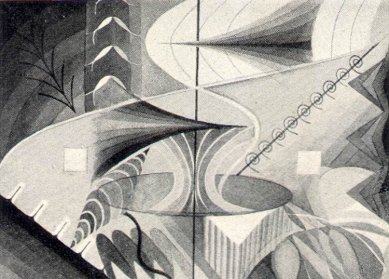

Years ago, I found myself in front of this painting in the Louvre, undisturbed by a crowd of foreigners in my admiration. The magically beautiful colors cannot be captured even by the most perfect reproduction. The brown parts of the landscape form a wave. The outline of the Mona Lisa is already set into the descending part of this quivering. The Mona Lisa is not a pleasing object in the common sense of the word. Striking is her resemblance to Leonardo, as if a drawn line connects them, as if the head of Leonardo was in the background of this portrait. This internal miracle of the painting is more effective than the moving eyes. This drawn line appears to me as a melody of death. Death plays even in the lights of her sleeves; the white chill sounds more insistently in the right hand, more muffled in the left. Muted colors capture her essence, and even the green color is not of this world. Perhaps the dimensional proportions of the painting heighten this feeling. The colors brown, reddish-brown, gray-brown, blue, blue-green and green-blue of the mountains, gray-green of the sky are the color scale of death. After an hour and a half of observing this painting, I understood the magical mixture of a smile with death. That day, I could not perceive other paintings, not even those of Raphael, Tintoretto, and Rembrandt. I wandered through the Louvre, seeking some sort of counterpoint to the Mona Lisa. I needed a different color scale to revive my senses. I found it in Boucher's Odalisque, in the colors of blue, wine red, gray-blue, white-gray... It is not a portrait of a woman; it is sensory femininity, a chord of life...

Years ago, I found myself in front of this painting in the Louvre, undisturbed by a crowd of foreigners in my admiration. The magically beautiful colors cannot be captured even by the most perfect reproduction. The brown parts of the landscape form a wave. The outline of the Mona Lisa is already set into the descending part of this quivering. The Mona Lisa is not a pleasing object in the common sense of the word. Striking is her resemblance to Leonardo, as if a drawn line connects them, as if the head of Leonardo was in the background of this portrait. This internal miracle of the painting is more effective than the moving eyes. This drawn line appears to me as a melody of death. Death plays even in the lights of her sleeves; the white chill sounds more insistently in the right hand, more muffled in the left. Muted colors capture her essence, and even the green color is not of this world. Perhaps the dimensional proportions of the painting heighten this feeling. The colors brown, reddish-brown, gray-brown, blue, blue-green and green-blue of the mountains, gray-green of the sky are the color scale of death. After an hour and a half of observing this painting, I understood the magical mixture of a smile with death. That day, I could not perceive other paintings, not even those of Raphael, Tintoretto, and Rembrandt. I wandered through the Louvre, seeking some sort of counterpoint to the Mona Lisa. I needed a different color scale to revive my senses. I found it in Boucher's Odalisque, in the colors of blue, wine red, gray-blue, white-gray... It is not a portrait of a woman; it is sensory femininity, a chord of life...

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment