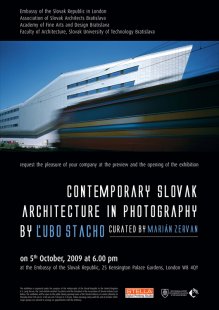

In London, Contemporary Slovak Architecture will be exhibited

Contemporary Slovak Architecture 1989-2009 in the Photographs of Ľubomír Stach

Embassy of the Slovak Republic, 25 Kensington Palace Gardens, London

The exhibition will open on October 5, 2009, at 6 PM and will last until the end of October.

Curator: Marián Zervan

Slovak architecture after 1989 is undergoing a complex and multifaceted process of self-renewal. After the dissolution of state-run and funded project institutes, private studios and workshops are re-emerging, and within them, an independent creative profession of architect is being reconstituted, which was often replaced by a designer. The restoration of professional status in the labor market, confirmed by the chamber, is one of the sources of differentiation in creative processes and opinions. The second is undoubtedly the diversity of architectural education. Before 1989, there were only two forms of architectural education: at technical schools and at art academies. Both forms were subject to state policy. After 1989, several architectural schools gradually emerged in major cities of Slovakia:

in Bratislava, Košice, and partly in Nitra, with autonomous accredited programs and led by significant architectural personalities. The third factor of differentiation is the opening of borders and the integration of Slovakia into European and world architecture. Before 1989, the state power imposed the official style of the Eastern Bloc known as socialist realism, which architects managed to resist only during certain periods, such as the 1960s. After 1989, a large number of creators with various individual styles appeared at the first annual exhibitions of the Architects’ Salons, which were not justified solely by returns to pre-war and interwar architecture or strong personalities at the schools, but also arose from their own experiences with world architecture in the form of internships, study and creative stays, as well as from numerous visits of famous architectural personalities to Slovakia. Last but not least, the diversity of contemporary Slovak architecture is also contributed to by galleries, research institutes, and architectural magazines and publications. Since 1989, not only small monographs of significant creators have been published but also synthetic books on Slovak architecture of the 20th century. Several individual and summarizing exhibitions and conferences and traveling exhibitions of Slovak architecture have been organized throughout Europe. As part of these, both authorial and critical polemics have been recorded, attempts at generational statements, and reevaluations of authorial initiatives. Finally, it is necessary to mention the entry of public discourse into architecture, which, with varying intensity, determines its movement. It is not just architectural competitions or battles for large projects between the state, private owners, and the architectural community, but also evaluations of environmental impacts and public participation, which are becoming increasingly taken for granted. Despite a certain conservatism of the public on one side and visionary thinking on the other, the societal and power influence on architecture cannot be underestimated.

All the aforementioned differentiating forces make the current architectural scene significantly diverse and difficult to describe with any overarching stylistic characteristics. Attempts to find fundamental contradictions in contemporary Slovak architecture between "late modernists," "postmodernists," or "neo-modernists" or between "new functionalists" and "organics" do not have much probative value regarding the state of Slovak architecture today.

Contemporary Slovak architecture is today value- and generation-richly stratified.

Alongside anonymous and commercial construction, we also observe the architectural routine of the mainstream and architectural kitsch. There are relatively few extraordinary architectural works, although awards for architecture are granted disproportionately frequently every year.

Currently, several third-generation Slovak architects of the 20th century are still working, including remarkable personalities like Ivan Matušík and Štefan Svetko. Although they do not build large constructions today, their orientation toward residential and family homes and housing complexes continues to inspire. The key projects after 1989 are taken over and gradually realized by the fourth generation of architects, among whom notable creators include Ján Bahna, Martin Kusý Jr., Pavol Paňák, as well as Branislav Somora and Fedora Minárik. Their names are associated with large high-rise administrative buildings, sacred architecture, but also substantial renovations. Some fifth-generation architects began in workshops with these figures, but are gradually becoming independent. This generation is associated with the greatest typological diversity and simultaneous assessment of architectural developments, particularly in the Netherlands. Several of them, born around 1966, aimed to establish a generational platform, but their initiative gradually disseminated into a multitude of the most diverse assignments: from family houses to multifunctional and residential complexes, memorials to sports halls and shopping centers. Notably, this generation advocates for greater representation of public buildings. Between the fourth and fifth generations stand out personalities such as Ľubomír Závodný, Juraj Polyak, Juraj Koban, Martin Kvasnica, and Márius Žitňanský, and Imro Vaško. The fifth generation is definitively associated with the names of Juraj Šujan, Peter Moravčík, and especially Boris Hrbáň and Andrea Klimková. The emerging sixth generation has shone in several major competitions and at both curatorial and authorial exhibitions. On one hand, it is characterized by the effort to establish a dialogue with major investors, which sometimes ends in compromise gestures, and on the other hand, is reflected in small architectural works or interventions within renovations and reconstructions. Here, within limitations, its creative potential is tested. Within this generational polarity, authors such as Kalin Cakov and Emil Makara or Benjamín Brádňanský and Vít Halada emerge.

The world of contemporary Slovak architecture is not just a realm of works, projects, designs, or exhibitions and presentations and discussions, associations, schools, and books. It is also an irreplaceable and definitive photographic record of this world.

For the visitor to this exhibition, a "reduced" architectural exhibition is offered on one hand. An exhibition without models, visualizations, and architectural drawings. An exhibition presenting not the processes of architectural thinking but their outcomes. It records not events but works. This "reduction" is, however, simultaneously a unique enrichment. Its viewer has the opportunity to experience the "record" of works of contemporary Slovak architecture from the second half of the 20th century and the first decade of the new millennium in the irreplaceable vision and atmosphere of the leading photographer of Slovak architecture Ľubomír Stach. This original creator, who divides his photographic work between authorial conceptual photography and architectural photography, offers an irreplaceable "introduction" to contemporary Slovak architecture for anyone who shows authentic interest.

Embassy of the Slovak Republic, 25 Kensington Palace Gardens, London

The exhibition will open on October 5, 2009, at 6 PM and will last until the end of October.

Curator: Marián Zervan

Slovak architecture after 1989 is undergoing a complex and multifaceted process of self-renewal. After the dissolution of state-run and funded project institutes, private studios and workshops are re-emerging, and within them, an independent creative profession of architect is being reconstituted, which was often replaced by a designer. The restoration of professional status in the labor market, confirmed by the chamber, is one of the sources of differentiation in creative processes and opinions. The second is undoubtedly the diversity of architectural education. Before 1989, there were only two forms of architectural education: at technical schools and at art academies. Both forms were subject to state policy. After 1989, several architectural schools gradually emerged in major cities of Slovakia:

in Bratislava, Košice, and partly in Nitra, with autonomous accredited programs and led by significant architectural personalities. The third factor of differentiation is the opening of borders and the integration of Slovakia into European and world architecture. Before 1989, the state power imposed the official style of the Eastern Bloc known as socialist realism, which architects managed to resist only during certain periods, such as the 1960s. After 1989, a large number of creators with various individual styles appeared at the first annual exhibitions of the Architects’ Salons, which were not justified solely by returns to pre-war and interwar architecture or strong personalities at the schools, but also arose from their own experiences with world architecture in the form of internships, study and creative stays, as well as from numerous visits of famous architectural personalities to Slovakia. Last but not least, the diversity of contemporary Slovak architecture is also contributed to by galleries, research institutes, and architectural magazines and publications. Since 1989, not only small monographs of significant creators have been published but also synthetic books on Slovak architecture of the 20th century. Several individual and summarizing exhibitions and conferences and traveling exhibitions of Slovak architecture have been organized throughout Europe. As part of these, both authorial and critical polemics have been recorded, attempts at generational statements, and reevaluations of authorial initiatives. Finally, it is necessary to mention the entry of public discourse into architecture, which, with varying intensity, determines its movement. It is not just architectural competitions or battles for large projects between the state, private owners, and the architectural community, but also evaluations of environmental impacts and public participation, which are becoming increasingly taken for granted. Despite a certain conservatism of the public on one side and visionary thinking on the other, the societal and power influence on architecture cannot be underestimated.

All the aforementioned differentiating forces make the current architectural scene significantly diverse and difficult to describe with any overarching stylistic characteristics. Attempts to find fundamental contradictions in contemporary Slovak architecture between "late modernists," "postmodernists," or "neo-modernists" or between "new functionalists" and "organics" do not have much probative value regarding the state of Slovak architecture today.

Contemporary Slovak architecture is today value- and generation-richly stratified.

Alongside anonymous and commercial construction, we also observe the architectural routine of the mainstream and architectural kitsch. There are relatively few extraordinary architectural works, although awards for architecture are granted disproportionately frequently every year.

Currently, several third-generation Slovak architects of the 20th century are still working, including remarkable personalities like Ivan Matušík and Štefan Svetko. Although they do not build large constructions today, their orientation toward residential and family homes and housing complexes continues to inspire. The key projects after 1989 are taken over and gradually realized by the fourth generation of architects, among whom notable creators include Ján Bahna, Martin Kusý Jr., Pavol Paňák, as well as Branislav Somora and Fedora Minárik. Their names are associated with large high-rise administrative buildings, sacred architecture, but also substantial renovations. Some fifth-generation architects began in workshops with these figures, but are gradually becoming independent. This generation is associated with the greatest typological diversity and simultaneous assessment of architectural developments, particularly in the Netherlands. Several of them, born around 1966, aimed to establish a generational platform, but their initiative gradually disseminated into a multitude of the most diverse assignments: from family houses to multifunctional and residential complexes, memorials to sports halls and shopping centers. Notably, this generation advocates for greater representation of public buildings. Between the fourth and fifth generations stand out personalities such as Ľubomír Závodný, Juraj Polyak, Juraj Koban, Martin Kvasnica, and Márius Žitňanský, and Imro Vaško. The fifth generation is definitively associated with the names of Juraj Šujan, Peter Moravčík, and especially Boris Hrbáň and Andrea Klimková. The emerging sixth generation has shone in several major competitions and at both curatorial and authorial exhibitions. On one hand, it is characterized by the effort to establish a dialogue with major investors, which sometimes ends in compromise gestures, and on the other hand, is reflected in small architectural works or interventions within renovations and reconstructions. Here, within limitations, its creative potential is tested. Within this generational polarity, authors such as Kalin Cakov and Emil Makara or Benjamín Brádňanský and Vít Halada emerge.

The world of contemporary Slovak architecture is not just a realm of works, projects, designs, or exhibitions and presentations and discussions, associations, schools, and books. It is also an irreplaceable and definitive photographic record of this world.

For the visitor to this exhibition, a "reduced" architectural exhibition is offered on one hand. An exhibition without models, visualizations, and architectural drawings. An exhibition presenting not the processes of architectural thinking but their outcomes. It records not events but works. This "reduction" is, however, simultaneously a unique enrichment. Its viewer has the opportunity to experience the "record" of works of contemporary Slovak architecture from the second half of the 20th century and the first decade of the new millennium in the irreplaceable vision and atmosphere of the leading photographer of Slovak architecture Ľubomír Stach. This original creator, who divides his photographic work between authorial conceptual photography and architectural photography, offers an irreplaceable "introduction" to contemporary Slovak architecture for anyone who shows authentic interest.

Marian Zervan

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment