WONDERLAND as a magazine - a platform for architecture

#1 Getting Started / Getting Started

www.wonderland.cx

|

However, we will not find any buildings in Wonderland. The magazine is not interested in presenting "what" from the world of architecture, but "how," which hides behind the realizations. Wonderland does not deal with renowned architectural firms, but with young and small teams. It uses its network as a relevant database of data to compare conditions for architects and architecture in Europe. The data sources also include local architectural chambers and European research. The intent of Getting Started—a guide full of facts and diagrams, advice, and experiences—is to serve as a manual for young European architects at the beginning of their careers. This project is ideally timed. The European construction and labor market has expanded to include countries from the Eastern Bloc. A first generation has emerged that grew up after the fall of the Iron Curtain and perceives this new Europe as their natural field of activity.

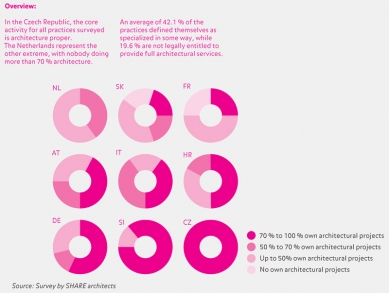

Getting Started focuses on 3 themes: place of operation, architectural profile, and marketing skills. These are the areas that every beginning architect should be able to navigate at the start.

CHOOSE YOUR FIELD

First and foremost, the choice of field is essential. Here, the project examines the possibility of an office existing in a metropolis or a small town, in the country of origin, or the consequence of mobility to work in several places simultaneously against the backdrop of economic indicators.

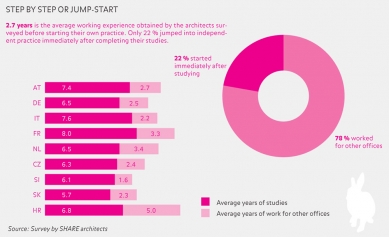

It compares the conditions for architects in different countries in Europe. The data includes the time required for architectural study, the duration of compulsory training for authorization, where exams are mandatory and where they are not, and how long a young architect practices before opening their office. Whether membership in a chamber is mandatory and what the fees are. The inconsistency of Europe is evident, for example, in the density of architects. While the ratio of the population to the number of architects is lowest in Romania (one architect for every 4,060 inhabitants), in Italy, there is one architect for every 516 Italians.

Study Time

The prescribed minimum study time for architects does not differ significantly among European countries. After graduating, a mandatory practice period in an architectural office is required, lasting a maximum of 5 years to obtain authorization. Nearly 45% of EU architects must take an exam to open their own practice in their country of origin.

|

DEFINE YOURSELF

The next chapter highlights the importance of defining the character of the studio. Various authors offer a collection of experiences and individual strategies.

Beware of the Concept (Eva Boudewijn)

A coherent architectural concept for a firm is essential, but an organizational concept is equally important. In a prosperous firm, architects need not only professional skills but also managerial and business skills. Wonderland characterizes different types of architectural firms. You just need to choose between studio, office and business. These three types employ different work methods and skills in varying proportions. It is about the combination of your talent and ambition with the structure, working method, and skills of your architectural firm¹.

Studio is a smaller formation whose distinguishing feature is a clear signature on the design strongly influenced by the leading personality/ personalities. Client demands often yield to the architect-designer's vision, who imposes their idea at all costs. Studio usually has issues with project management.

Office is a firm where risk is minimized. An optimal compromise is sought between client demands and aesthetic qualities. These offices are the most common type.

In Business, technical expertise and product quality are paramount. Maximum efficiency, speed, time, construction standards, and feasibility are the main priorities from the start of the project. Business operates like a well-oiled architectural machine. These are merchants who are able to make architecture a profitable business.

Team Identity or One-(wo)man Show

2.3 partners is the average size of a Wonderland-type practice. Most practices are led by 2 to 3 partners, 21% are one-(wo)man shows, and 10% have more than 3 partners.

Profile of a typical small design-oriented architectural practice in the EU.

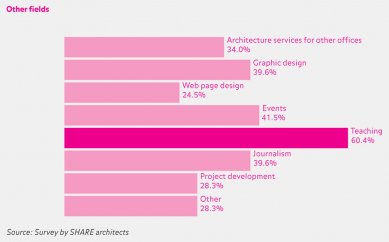

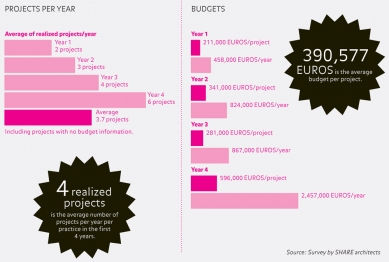

The average architectural practice is a collective effort. Partners typically establish a studio on average after 6.9 years of study and 2.7 years of working for another office. Their initial investments in the first year are less than 10,000 Euro. Most orders come from personal contacts. Every second practice is also involved in another area besides architecture. Participation in international competitions, working on projects abroad, and running a studio in more than one country is common.

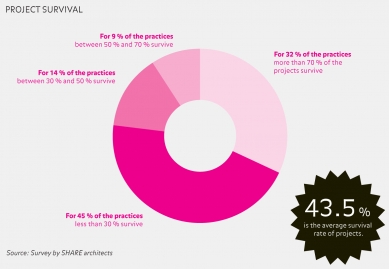

Half of initiated projects ultimately do not get realized. Studios typically work unpaid overtime, at least on selected projects, and half of the cases work an unlimited number of hours just to produce the best design².

|

1) Eva Boudewijn: Mind Your Design, Motion Consult Amersfoort

2) Source: Research by SHARE architects

Poaching (Paul Rajakovics)

In the construction business, an intellectual approach to design increasingly poses a certain risk to the return on investment. There are forecasts suggesting that interest in designers will transform over time into interest in speculators who can maneuver through the game of contract penalties and generate the best price for the client. This may maximalize the reduction of design. Here, the question arises: how to reintegrate creative potential back into architecture? This problem is responded to by OMA with a new approach to the architectural assignment. The creative potential is no longer seen in architecture or urbanism, but in their reassessment. This potential is directed towards local authorities and developers. OMA has created the branch AMO—a think tank, a research team for programs and counter-programs. It connects marketing with the impacts of globalization. AMO is the economic factor of OMA. Its consequence is contracts with Prada, Ikea, or Volkswagen.

This structure of firm operation is excellent. However, why are there so few successful imitators?

Wonderland seeks answers by analyzing OMA's special status. The unique position among firms has been created by presenting themselves in the media as a global player and acting as a leading authority at Harvard. A special feature of OMA is the anachronistic approach to problems. On this basis, they established an office that was unique at the time of its inception. A Dutch architect, who served as a screenwriter and journalist, an artist, and two Greek architects. This founding team combined know-how from different professions and cultures, enabling them to tackle problems from a broader perspective. At the top of this pyramid is Koolhaas, leading young architects willing to work hard for the opportunity of poaching skills and know-how.

The image of the architectural profession is changing. Architecture has always been presented as a profession of versatile individuals. Even today, we encounter opinions from architects that architecture is a superior discipline, an all-encompassing art. However, the pressure on the individual, who should be capable of everything independently, has massively increased. As a result, specialization in architecture has become common practice: architectural offices collaborate with project managers or design offices. Although it is beyond the capability of a single person, the architect-designer prefers to see themselves above all this. Le Corbusier elevated the architect to the position of the ingenious superman, understanding aesthetics, in promoting the profession. He is an elite of society, open to everything.

Team vs. Lone Warrior. Wonderland's survey clearly indicates that most architects no longer work individually but in teams. The team is a consequence of the change in perception of the architectural profession. It can effectively operate on the market as a brand while maximizing benefits from the division of labor. The team typically also includes other sectors, whose contributions are integrated into architectural projects. Lone warriors, following the example of Corbusier, have no place here because they consistently perceive architecture as a superior discipline. The team has gained essential roles in the architectural world thanks to current economic parameters. A small and well-coordinated team is more flexible and adaptable to changing conditions than a large architectural firm with many highly specialized experts. The team also requires a certain social intelligence and balanced ego advocacy. Since there is a financial vacuum between tendering and realization, some team members may need to supplement their income by working in other studios or teaching. Teams do not arise solely out of necessity. The added value of teamwork has finally been recognized as the only way to meet the current complex demands of the architectural profession.

In any case, teamwork serves as the best foundation for poaching in other fields without leaving the realm of architecture.

Groups emerged even in the revolutionary 60s. A collective as a new strategy for self-presentation. The idea, born from the youth culture of the time, opposed the classical concept of the architectural profession. Impersonal names indicated the superiority of the collective over the individual ego. Their manifestos were more easily communicable through art and academic activities than through buildings. Archigram, Superstudio, Coop Himmelb(l)au, Ant Farm... Most of the groups dissolved by the end of the 70s.

Paul Rajakovics describes the phenomenon of architectural "pop groups" as a Europe-wide movement of the 90s. The groups of the 90s intervene/poach in the fields of art, culture, exhibitions, and urban interventions. The different backgrounds of individual members define interesting interdisciplinary areas of operation. For example, the studios include: Propeller Z (Austria, architecture/ industrial design/ graphic design), Stalker (Italy, art/ architecture), Crimson (Netherlands, architecture and research).

HOW TO STAY IN BUSINESS

The third and final chapter maps the tension between finances, quality, and time. It analyzes marketing strategies and the unequal relationship between media attention and economic success.

What is important and must be learned on the go is the ability to trade, negotiation skills, the ability to build trust, time management, and marketing in all its forms.

In the interview Negotiating Between Aesthetics and Client Demands, Eva Boudewijn analyzes the triangle: the intertwined relationship between quality (good), budget (cheap), and design (fast). The client wants the highest quality product, the cheapest, and preferably the quickest. The resulting effect also depends on the architect's ability to convince the client of the quality of their design or vision. For this, the architect must be equipped with excellent communication skills, create a credible relationship, and avoid conflicts.

How to Keep Up?

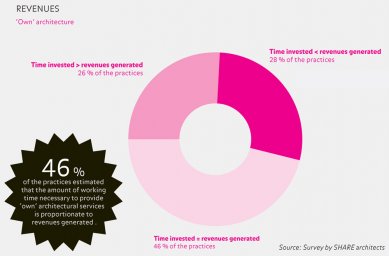

No other profession requires as much skill to create a meaningful balance between invested time, achieved quality, and earned money. Of the 58 surveyed practices, 95% admit they offer part of their work for free. At the same time, they increase working hours to 51 hours per week, and the average project survival rate is estimated at less than 50%. Clients are hard to find and easy to lose. Media success is not a guarantee of business success.

|

Dance of the Marketing Mix (Tore Dobberstein)

There is no manual or handbook on marketing taught in schools. Tore Dobberstein, an economist and partner at the architectural firm Complizen, offers a small alphabet of marketing for architects.

In today's architectural market, there are more providers of design services than there is demand. Should architects then offer their product using advertising methods, manipulating and brainwashing? The problem is that there is no way to manage according to any uniform marketing doctrine. Architects offer services that overlap three basic marketing categories: product marketing, investment marketing, and service marketing.

In relation to market competition, we need to have an image of a trendy brand that everyone wants to possess. Given the investment risks that our clients are taking, we need reliable professionals. At the same time, we must ensure client satisfaction, which depends on the extent of our agreement with their wishes. Just like in a massage salon, we must willingly mediate the service and fulfill the client's desires.

According to such a definition, architects should abandon their ideals and values in favor of ruthless commercialization. This is not the way forward. Moreover, we all know that it is precisely ideals and personal values that have brought successful colleagues to the forefront.

At the beginning of an effective architectural marketing strategy, we must answer strategic questions. What do I stand for? Where do I want to take it? The answer is self-definition. It is important that we are able to present our clear and coherent image, corporate identity. This concerns all aspects of our practice—from working materials, office, portfolio, business cards, lectures to web presentations, articles in magazines, etc. Only when we have created this identity is it time to enter the world of marketing. Here, we can adhere to the marketing doctrine commonly known in the business world as the 4 Ps: Product, Price, Place, and Promotion.

What is the product we offer? As previously mentioned, the current trend is to expand the areas of operation. By linking architecture with galleries or design shops, teams such as the German Blauraum Architekten or the Slovak Fabrica are thriving. These formations did not arise as a consequence of economic pressure. Product innovation results from the architect's entrepreneurial and artistic endeavors.

Price is also an essential marketing tool. In several countries, architects are required to associate in unions or chambers that specify working conditions and regulate prices through pricing lists and regulations to prevent price competition. Architects appreciate these regulations, as competition tends to undercut prices, often leading to a low-quality product. However, the issue remains the measurability of architectural quality.

In the area of promotion, our online presence is crucial. Equally important is the language we use to communicate with potential clients. Clients generally have not studied architecture. Besides wanting them to understand, we must also appeal to them emotionally. Architecture is often a luxury product, and such a product should be sold more through subtle finesse than rational arguments. Among architects, there exists an unwritten ban on advertising, which ultimately is less effective. For this reason, and not only among architects, public relations and sponsorship are gaining importance. New opportunities for engagement open up continuously.

New strategies also include the right choice of place. How and where can we find clients? How and where can they find us?

Currently, the often-cited network works well. The more diverse the network, the more successful the distribution. Successful collaborations between groups of architects, designers, artists, and computer experts are occurring. An exclusively architectural network like Wonderland is not the best example of how to create an effective sales network capable of reaching more potential clients.

Contacts are also very important. For young practices, family and close friends are often the first clients. This is based on trust. Architecture is a commodity of trust. How to gain credibility? In personal life, we build trust in people through socializing, forming relationships, and in many cultures, dance is still used for this purpose. What to do when we cannot drink or dance with all our potential clients? The answer is our constant presence in society; this is paramount from a marketing perspective. In addition to social influence, it is also important to activate others, to build cultural, personal, and psychological bridges. Civic engagement and active participation in social life are classic (marketing) activities employed by successful entrepreneurs. By employing these strategies, we may succeed in transitioning from an introverted practice to an extroverted one.

Product

78.6% of the surveyed practices claim they are willing to compromise between the desired project quality and what can be achieved with a specific client. 30.4% place no conditions: any budget and client is acceptable. 12.5% pursue excellence and design exclusively: if that is not feasible, they will decline the commission. 49.1% of practices are able to work unpaid overtime to achieve the best possible design. Only 24.5% limit their effective working time to paid hours.

Pricing

62% consider their prices to be at market level, 21% go below price, 11% go above. In all this, only 17% strictly adhere to the pricing list of the chamber or another professional organization. 96% offer certain work for free. At least 15.6% take commissions, even with the knowledge of possible losses.

Place

38% primarily work in the local market, 42% do not distinguish between local, national, and international markets. 11% mostly work on international projects.

Promotion

Only 3.6% hire a marketing and public relations professional. 7.3% want nothing to do with that, while 85.5% try to publish and market on their own.

|

Fame Will Not Save You (Michael Obrist)

When Le Corbusier, Cook, Eisenman, Koolhaas, or Zaha Hadid formulated their manifestos, they were relatively young—between 25 and 35 years old. It was easier for them to express themselves in another medium—artistic or scientific. Thanks to professional journalism (and later mass media), they contributed to the global discourse and found their place in the spotlight. However, the social circumstances under which this occurred are unpredictable. Behind the fame, we find little-discussed taboo questions:

How did they earn a living? How can media success change a profession and the circumstances of production? What consequence does the attention economy have on young teams? What were the changes that occurred as a result of pushing the boundaries of the architectural discipline?

The author of this essay is an architect from the Viennese feld72—a collective for architecture and urban strategies. He teaches conceptual architectural strategies (Linz). He references The Attention Economy (Die Okonomie der Aufmerksamkeit) by Georg Franck. In a mediated world, attention leads to social capital that creates a market. Not a financial upheaval, but revenues from attention helped certain sectors achieve global importance. This employs two different marketing tools: 1. the exchange of professional services for wages, 2. the exchange of published opinions for the attention of those interested in culture. According to Franck, architecture also utilizes these tools.

Obrist, however, points out that in architecture, there is no direct correlation between wages and media attention. Even Rem Koolhaas addresses this issue. On one hand, there are sectors producing culture (painting, sculpture, film, acting, sports...) where the impact of media success is reflected in their economic situation. The architectural world is on the other side, where this is not the case. Income remains laughably low in relation to the added value of the product that arises from fame. According to Koolhaas's concept, for example, Frank Gehry should receive a percentage of Bilbao's annual income. Since this concept is unrealistic, the only return on fame for the architect remains their reputation. Society circulates— we value what we pay attention to, and we pay attention to what we value.

Franck's theory obscures the fact that even the most remarkable moments of reputation rarely had a direct impact on an architect's economic situation. Haus-Rucker-Co achieved media success and made it to Documenta, but in their professional lives, they still sought survival strategies. They changed jobs, engaged academically. They pushed the boundaries of the discipline into the realm of art. The current generation also takes advantage of this crossover. Placing a work or event in the realm of art defines its value.

Return on Investment (Astrid Piber, Hannes Pfau)

|

The houses realized by Wonderland teams confirm the general trend: the average price per m2 is around 780 Euro in Eastern European countries, while in Western European countries, it is around 1,430 Euro.

Wonderland is a sophisticated compilation of knowledge. It stems from the fact that the European wonderland is beginning to be our common field of operation. However, Czechia or Slovakia often do not share the parameters of a typical young European practice. We represent the smaller percentage in the graph of economically less prosperous countries of the "new" Europe. But we can take comfort in the fact that the challenges faced by our young studios are the same everywhere in Europe.

In late January 2007, the second issue of Wonderland will be on sale, dedicated to how architects deal with mistakes.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment