Sedesowce - Wroclaw's Manhattan

Residential and service complex at Grunwaldzki Square in Wrocław

The city of Wrocław (in Polish, Vratislav, in German, Breslau) transformed into a fortified place (Festung Breslau) at the end of World War II, which was meant to serve as a base for further Nazi counterattacks and, later, to hold back the Red Army during its march towards Berlin as the war drew to a close. In late February 1945, when the Soviets occupied Gadów airport, the Nazi administrator of the Prussian area, Karl Hanke, issued an absurd order to demolish the northeastern suburb of Wrocław and quickly construct a new runway measuring 300 x 1300 meters. For this purpose, the block development of residential buildings from the 19th and 20th centuries along the former Kaiserstraße (now Grunwaldzki Square) was leveled. During the construction, thousands of forced laborers died. The airport never began functioning. On May 6, 1945, the last defenders surrendered, the German population had already fled or been evacuated, and new residents, mostly from Lviv, moved into Wrocław. Due to uncertainties about whether the original inhabitants would return (these fears persisted among Poles until the 1970s), Wrocław did not see immediate renewal after the end of World War II. Some buildings were even dismantled, and the construction materials were transported to repair the destroyed Warsaw. Although Wrocław was heavily affected by the war, a significant portion of buildings had to be demolished later due to a lack of maintenance, as rainwater began leaking into roofless houses and wooden ceilings started to collapse.

The wide cleared strip from the Grunwaldzki suspension bridge to the former square (still an important transport hub) Grunwaldzki Square became a unique opportunity for urban planners to design a new district intended for up to 200,000 residents near the historic center. The first projects emerged as early as the late 1940s, during the peak of socialist realism heavily influenced by Soviet ideology associated with the celebration of the Stalin cult. On the southern side of Grunwaldzki Square, between 1950 and 1955, strictly symmetrical buildings D-1 and D-2 for the Wrocław Polytechnic were built in the spirit of socialist realism. The authors of these massive structures, which could easily be mistaken for Nazi architecture, were Tadeusz Brzoza and Zbigniew Kupiec, who at that time also served as the dean of the Faculty of Architecture at the local technical university. After Stalin's death, political climate relaxed throughout the Eastern Bloc, abandoning the architectural classicizing doctrine, and opened the space for modernists. One of the first harbingers in Wrocław was the modern accommodation for scientific workers, Dom Naukowca (1956-61), which was constructed in close proximity to the monumental D-1 and D-2 buildings. The project involved Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak, as well as Edmund Frąckiewicz, Maria Tawryczewska, and Igor Tawryczewski. The building, with a relaxed base, spacious apartments, and dynamic horizontal partitioning complemented by bright yellow balconies, could not be in greater contrast to the neighboring socialist block. The architect lived in this building for a long time (until she built a family house on Kochanowskiego Street in the late 1970s/early 80s).

Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak was also the author of the apartment building "Galeriowiec / Mezonetowiec" (1956-62, reconstruction 2017) located near the main railway station. The design, featuring walkways, protruding communication cores, and duplex apartments, clearly drew inspiration from Le Corbusier's housing machines.

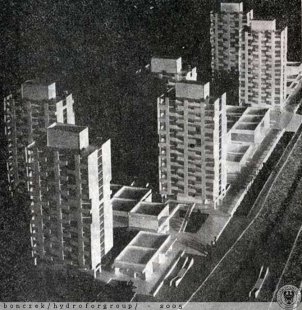

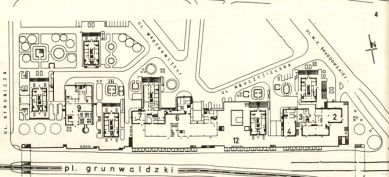

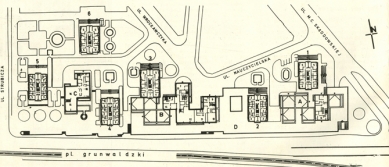

In the early 60s, planning began for the development on the northern side of Grunwaldzki Square according to the urban design by Tadeusz Brzoza. In 1963, Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak was tasked with designing the apartment buildings.

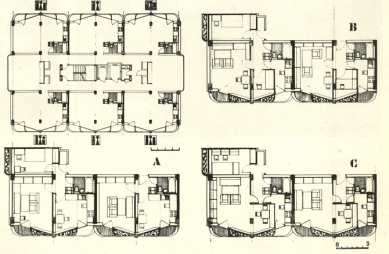

The originally envisioned six twelve-story buildings grew to an additional four floors. Within five years, six different variants were created. In 1967, the final version of a self-sufficient urban district with an elevated platform separating pedestrians from vehicular traffic was approved. After the completion of the first two high-rise buildings, the project was suspended due to a lack of financial resources. At that time, the focus was more on quantity rather than quality in terms of completed housing units. Only when the high-rise buildings, along with the Mezonetowiec house, were featured in the French magazine L'Architecture d'Aujourd'hui and at an exhibition in Paris did foreign experts start to take interest in the project, and Polish politicians recognized that the entire micro-urbanism should be completed and presented as one of the successes of socialist architecture. Originally, there were no plans to build a podium where shops, services, and community spaces were to be located. All these components, which turned the housing estate into a vibrant urban quarter, were pushed through by Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak only after long negotiations. The wide outdoor stairs leading to the elevated platform with a series of shops, restaurants, cafes, and bars provided an unprecedented backdrop. The entrance lobbies to the apartment buildings with marble floors and wooden paneling represented a significant standard in the contemporary Eastern European production. Not everything could be completed as originally intended. The rounded prefabricated panels on the façade were originally not intended to function as balconies but merely to create a recessed layer helping with shading. During the reconstruction in 2017, the original brutalist character of the exposed concrete of the prefabricated elements in combination with the brown ceramic cladding faded away. The entire complex still remains a shining example of Polish modernism and an unmistakable symbol in the Wrocław skyline. However, not everyone has come to terms with the buildings, and among the residents, in addition to comparisons to Manhattan, they earned derogatory nicknames such as "bunkers" or "toilet seats."

The broader international recognition of the author of the Wrocław high-rise buildings came only posthumously when her lifelong work was presented in the Center for Architecture AIA in Manhattan in the spring of 2019.

The wide cleared strip from the Grunwaldzki suspension bridge to the former square (still an important transport hub) Grunwaldzki Square became a unique opportunity for urban planners to design a new district intended for up to 200,000 residents near the historic center. The first projects emerged as early as the late 1940s, during the peak of socialist realism heavily influenced by Soviet ideology associated with the celebration of the Stalin cult. On the southern side of Grunwaldzki Square, between 1950 and 1955, strictly symmetrical buildings D-1 and D-2 for the Wrocław Polytechnic were built in the spirit of socialist realism. The authors of these massive structures, which could easily be mistaken for Nazi architecture, were Tadeusz Brzoza and Zbigniew Kupiec, who at that time also served as the dean of the Faculty of Architecture at the local technical university. After Stalin's death, political climate relaxed throughout the Eastern Bloc, abandoning the architectural classicizing doctrine, and opened the space for modernists. One of the first harbingers in Wrocław was the modern accommodation for scientific workers, Dom Naukowca (1956-61), which was constructed in close proximity to the monumental D-1 and D-2 buildings. The project involved Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak, as well as Edmund Frąckiewicz, Maria Tawryczewska, and Igor Tawryczewski. The building, with a relaxed base, spacious apartments, and dynamic horizontal partitioning complemented by bright yellow balconies, could not be in greater contrast to the neighboring socialist block. The architect lived in this building for a long time (until she built a family house on Kochanowskiego Street in the late 1970s/early 80s).

Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak was also the author of the apartment building "Galeriowiec / Mezonetowiec" (1956-62, reconstruction 2017) located near the main railway station. The design, featuring walkways, protruding communication cores, and duplex apartments, clearly drew inspiration from Le Corbusier's housing machines.

In the early 60s, planning began for the development on the northern side of Grunwaldzki Square according to the urban design by Tadeusz Brzoza. In 1963, Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak was tasked with designing the apartment buildings.

The originally envisioned six twelve-story buildings grew to an additional four floors. Within five years, six different variants were created. In 1967, the final version of a self-sufficient urban district with an elevated platform separating pedestrians from vehicular traffic was approved. After the completion of the first two high-rise buildings, the project was suspended due to a lack of financial resources. At that time, the focus was more on quantity rather than quality in terms of completed housing units. Only when the high-rise buildings, along with the Mezonetowiec house, were featured in the French magazine L'Architecture d'Aujourd'hui and at an exhibition in Paris did foreign experts start to take interest in the project, and Polish politicians recognized that the entire micro-urbanism should be completed and presented as one of the successes of socialist architecture. Originally, there were no plans to build a podium where shops, services, and community spaces were to be located. All these components, which turned the housing estate into a vibrant urban quarter, were pushed through by Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak only after long negotiations. The wide outdoor stairs leading to the elevated platform with a series of shops, restaurants, cafes, and bars provided an unprecedented backdrop. The entrance lobbies to the apartment buildings with marble floors and wooden paneling represented a significant standard in the contemporary Eastern European production. Not everything could be completed as originally intended. The rounded prefabricated panels on the façade were originally not intended to function as balconies but merely to create a recessed layer helping with shading. During the reconstruction in 2017, the original brutalist character of the exposed concrete of the prefabricated elements in combination with the brown ceramic cladding faded away. The entire complex still remains a shining example of Polish modernism and an unmistakable symbol in the Wrocław skyline. However, not everyone has come to terms with the buildings, and among the residents, in addition to comparisons to Manhattan, they earned derogatory nicknames such as "bunkers" or "toilet seats."

The broader international recognition of the author of the Wrocław high-rise buildings came only posthumously when her lifelong work was presented in the Center for Architecture AIA in Manhattan in the spring of 2019.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment